|

Introduction by Jim Liddane

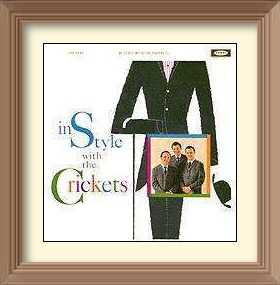

A top-class musician with several Gold Discs to his credit in his own right....A former disc jockey and later the owner of two successful radio stations....A producer with nine American hits by one act alone in the space of 18 months

The person responsible for the biggest selling record of the year 1963....A publisher who opened his studios to all on a "per-song" and not "per-hour" basis....A manager who guided the career of one of the giants of rock music

A writer who penned several hits, including some genuine standards....A man who for many years, suffered an organised campaign of slander....But above all, a gentleman, whose genius is only now being recognised by the music industry

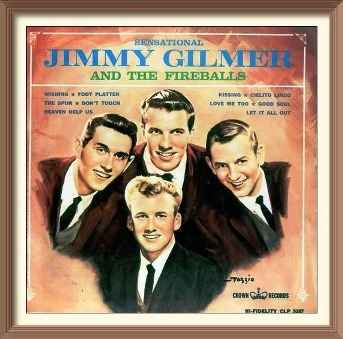

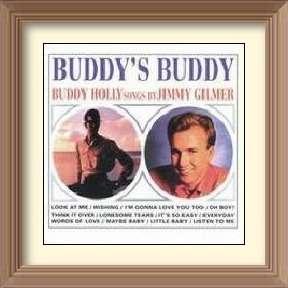

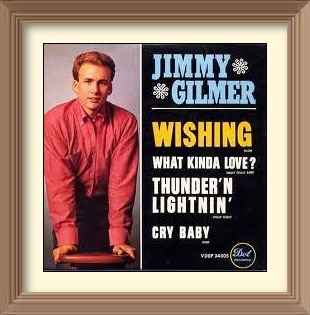

The man? Norman Petty, whose studio recorded such greats as Roy Orbison, Buddy Knox, Jimmy Bowen, Buddy Holly, Trini Lopez, Jimmy Gilmer, Bobby Vee, The Crickets, LeeAnn Rimes, The Fireballs, and many more.

Norman rarely gave interviews, but I spoke with him for the International Songwriters Association over a protracted period. Some of the original transcript remains unpublished at the request of Norman Petty.

Norman Petty was born in the small but attractive town of Clovis, New Mexico, on May 25th, 1927, the youngest son of Sidney and Thelma Petty.

Clovis was a nice town to grow up in according to Norman, and he never lost his affection for the area. Years later, he bought several homes in different parts of Clovis, investing in jewellery stores and two radio stations in the town. Although he enjoyed travel, he said that he never had any wish to live anywhere else except Clovis.

The Petty family operated a garage in the town, and both parents, according to Norman, were musically proficient. Norman's Dad was not just a highly-regarded motor mechanic, he could turn his hand to fixing anything, electrical or mechanical, but in particular, radios and cameras.

Norman however showed little interest in the garage as a child. Instead, he taught himself to play the piano at an early age, and encouraged by his father, also experimented with amplifiers, radios and indeed any other electrical equipment he could lay hands on. On discovering that he had been born with "perfect pitch", he even learned how to tune pianos, earning pocket money tuning the piano at Clovis High School.

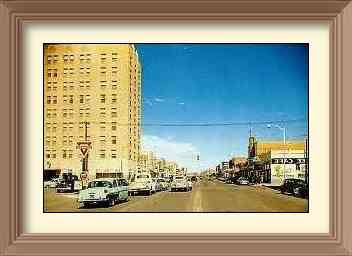

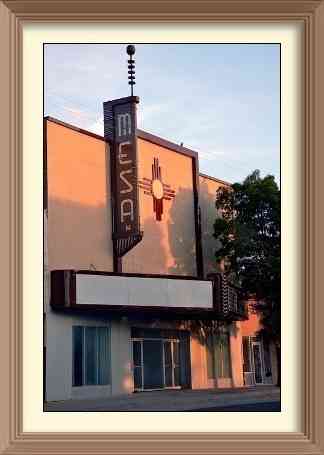

Downtown Clovis 1953

When he himself entered High School, Norman formed his first combo, the Torchy Swingsters, which played dance music for fellow pupils. Practices were intense occasions one band member recalls, with Norman recording their performance, and then critiquing what he heard. The outfit soon found themselves in demand not just at the school but at the nearby Clovis Air Force Base (later renamed the Cannon Air Force Base), performing for soldiers and airmen who were about to ship out to the Pacific.

Norman loved the Cannon base, travelling out there in his spare time to watch aircraft taking off and landing. This affection for the US Air Force was to remain. Within a few years, he was doing his own military service at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia, while some ten years later, the Norman Petty Trio was found regularly performing for the top brass at dozens of Air Force bases across the United States.

Lyceum Theatre, Clovis

By the time he was thirteen, in addition to playing every weekend around Clovis, Norman was holding down two jobs after school - as a projectionist in a local cinema, the Lyceum, and as a pianist - playing requests over his local radio station KICA, and later as a disc jockey on the station.

KCIA had gone on air in May 1932, originally from the Woolworth Building in downtown Clovis, moving later to the Hotel Clovis site where "Norman Petty, KICA’s popular disc jockey, brings Musical Mailbag to the air twice daily. Popular with all the high school youngsters, Norman finds that many of his requests are coming from housewives as well".

Although he was (by his own admission) shy to the point almost of brusqueness and constantly nervous when called upon to read out requests, he loved the atmosphere at the radio station. and the opportunities it gave him to examine the studio equipment, and to meet and mix with other more mature performers.

Both his radio and cinema jobs paid about the same amount of money, but destiny was about to play its part.

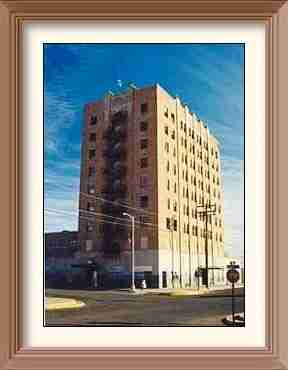

Hotel Clovis, Clovis, HQ for KICA Radio

"One afternoon, the announcer who, shall we say, enjoyed the juice too much, failed to show up to read the commercials on my request programme.

The lady at the desk handed me the commercials and just told me to read them. Naturally I protested but she just insisted saying that the sponsors had bought time on my show, and if the announcer was not going to turn up, then I would have to read them. Well I did of course, and I'm sure they sounded just terrible.

Anyway, after the broadcast was over, I was informed that the station manager wanted to see me. I decided that I was about to get fired, but instead, he offered me a job as an announcer.

Well, I was making about $7 a week as a projectionist, and they offered me three, or perhaps four times that, so naturally I took it! Within a couple of months, I was a fully-fledged disc jockey.

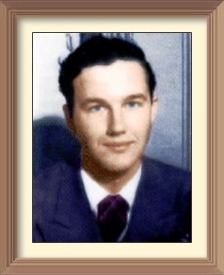

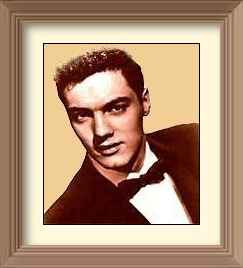

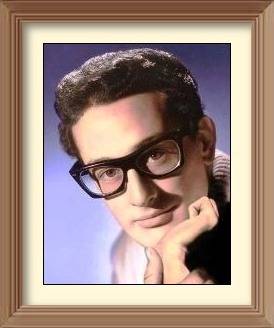

1943 KICA Radio publicity picture

of 15 year-old Norman Petty

Now the station I was with was the only one for miles around and so we naturally tried to please everybody. You might find yourself playing classical music, western swing, big band music, and what have you, throughout the one afternoon, and that was a fantastic indoctrination into the world of music as far as I was concerned. I think that it enabled me to enjoy, and play, all kinds of good music".

In 1943, when he was just fifteen, Norman was introduced by classmate Bill Pickering to Violet Ann "Vi" Brady who was a year behind them at Clovis High School but who was already regarded as one of the most promising young classical pianists in New Mexico. She lived just a few blocks away from Norman's home, and like Norman, she came from a musical family, while her uncle, a professor at the School of Music at the University of Oklahoma, was a frequent visitor to the town.

The two teenagers started dating, but although Norman remembers that they spoke constantly about music, rarely played piano in public as a duo. "A combo with two pianists would have been", as Norman joked to me, "a combo with one pianist too many!"

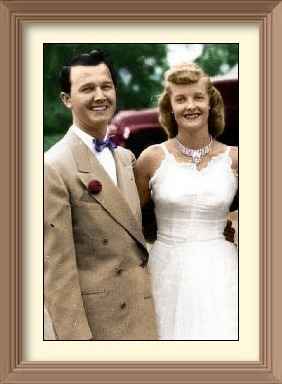

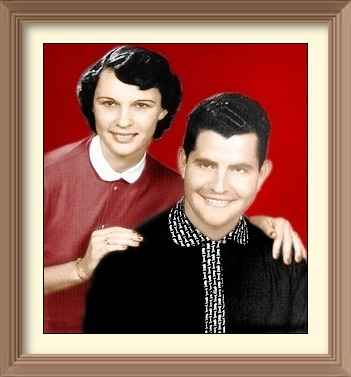

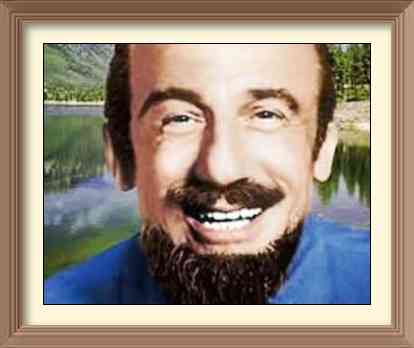

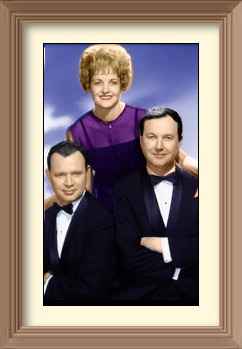

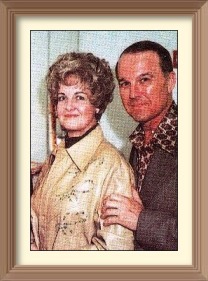

Vi & Norman

Meanwhile, the Torchy Swingsters had become Norman Petty & His Swing Kings, and then the Norman Petty Big Band, but just as he began to plan the launching of the Norman Petty Orchestra(!), he ended up in the US Air Force, and was despatched to do his military service to Langley Air Force base in Virginia.

While at Langley, Norman got the opportunity play a Hammond organ. Petty had played organ before this at the First Baptist Church on Gidding Street, but he had always regarded it as an instrument suitable only for sacred music. Now he had discovered the Hammond, and from then on, he rarely played piano, perhaps realising that although two pianos might indeed be one piano too many, an organ and a piano could blend together beautifully.

When Norman was discharged from the Air Force, he returned to New Mexico to enrol at the Eastern New Mexico University in Portales, just twenty miles away from Clovis, travelling home on weekends to set up the first incarnation of what would become the Norman Petty Recording Studios at the rear of his father's garage. Initially, it was a very basic operation, but still the first of its type in Clovis.

Norman told me that he did not see it initially, as a lifetime career. He had in fact looked at the possibility of raising finance to purchase outright or else buy into a radio station in Clovis, but after discovering that the investment being demanded was increasing every time he enquired while the advertising market in Clovis seemed to be narrowing every time he checked, he shelved the project for the time being. However radio remained for him an abiding passion, and Norman eventually realised his teenage dream when he set up KTQM in Clovis some seventeen years later.

Norman Petty Studios, Clovis, New Mexico

The makeshift studio made mainly speech-only acetates for local politicians running for election, for parents wanting to send "voice letters" to their sons serving overseas or perhaps record their childrens' voices for posterity, and for business owners eager to have their own voices advertising their goods on the radio, but it soon began to attract solo musicians and vocalists from both Clovis and its environs. Norman also offered to record wedding ceremonies, using another of his acquired talents in photography, to boost his income.

Meanwhile, Violet Ann Brady, was majoring in music at her uncle's University of Oklahoma, and during the Christmas break of 1947, the couple became engaged. On 20th June 1948, less than one month after Norman's 21st birthday, they married, moving into a small apartment attached to the rear of the garage-cum-store-cum-recording studio.

Norman now teamed up with a friend, guitarist Jack Vaughn, who had moved to Clovis from Lubbock. A former professional baseball player, he along with Norman and Vi formed The Three Musical Tones (described by Norman laughingly as the "worst band name ever chosen by anybody"). Shortly they would become the Norman Petty Trio, featuring Vi on lead vocals, with tight close harmony accompaniment from Jack and Norman, which would soon found itself playing weekend dates back at the Cannon Air Force base, and occasionally further afield.

Norman & Vi

However, the studio was making little money, and so the couple were mainly depending on the Saturday night gigs and Norman's work at KCIA. But even that was not secure, as Norman explained.

"I think I established some sort of record with that station, in that I was fired by them three times. The third time, I decided that they were trying to tell me something!

We left Clovis. and moved to Dallas where I had been offered a job playing organ on the now-defunct Liberty Network.

A booking agent who had heard me play in Clovis and had offered to get us work if we ever went on the road, contacted me again, and soon we began to play country clubs, officer's clubs, hotel rooms, NCO clubs, resorts etc., in that area.

I was also working as a part-time recording engineer for Jim Beck, who had a recording studio in Dallas which catered for all the big western stars like Ernest Tubb.

Actually, those were really marvellous times for us: Jim Beck was really kind to Vi and myself, and of course, I was picking up valuable experience working in the studio".

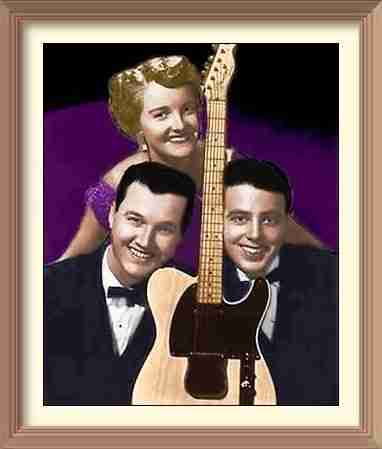

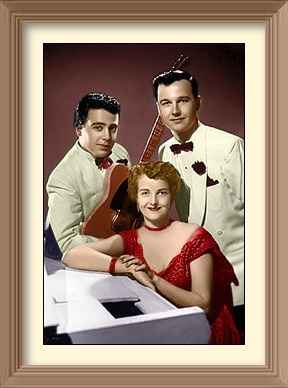

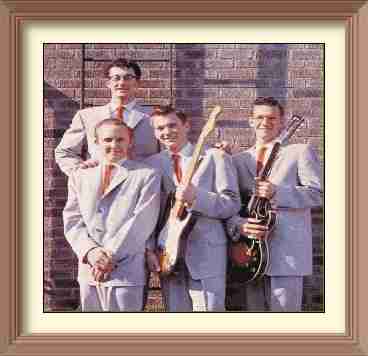

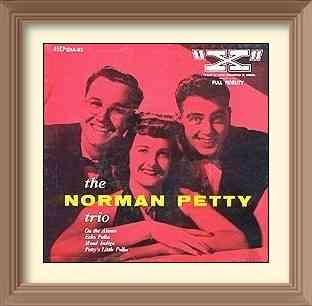

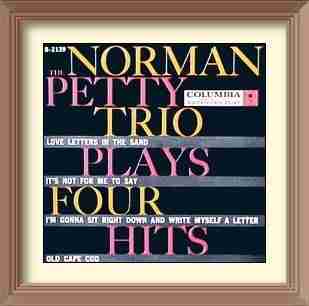

Norman Petty Trio 1954

Jim Beck had recorded many of the country greats including George Jones, Ray Price, Floyd Tillman, and Marty Robbins as well as having discovered Lefty Frizell, and was regarded by many as a recording genius.

Norman told me that of all the people he met in those days, Jim Beck was the one who had the biggest influence on him.

On the couple's return from Texas, Norman's studio project was re-activated, and the group (through Norman's old service contacts) began a series cross-country tours of American Air Force bases, taking residencies where they could find them, even spending a stint in Hollywood, and returning to Clovis every so often to meet up with family and open the makeshift studio for a few days. This pattern was to be their lifestyle for the next few years.

Norman Petty Trio 1954

The Norman Petty Trio became Norman Petty & His Trio for a period with the addition of Vi's cousin, vocalist Georgiana Veit and meanwhile, Norman was carefully building up his collection of audio equipment, even taking a recording machine on the road with the combo, initially using it to rehearse new tunes for their repertoire.

Members of the audience often asked if they could purchase a recording of the Trio, but up to this, Norman's combo had not released any records. One of the Trio's most requested tunes was a vocal version of the standard "Mood Indigo" which featured Vi on lead vocals, and Norman and Jack on harmony.

On Christmas Eve 1953, as Norman recalls, they recorded their own version "in a Jackson, Michigan, hotel dining-room". Unable to persuade any mainstream label to release the recording, Norman eventually pressed some discs on their newly-founded NorVaJak label, partly to sell at performances, and partly to gain radio airplay.

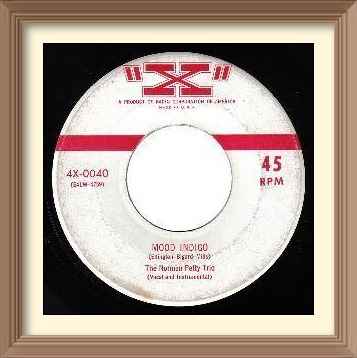

"Mood Indigo" on X Records

A division of RCA - X Records - eventually picked up on the recording, and released it nationally. It gave the Norman Petty Trio its first hit, selling just over half a million copies, reaching Number 1 in some areas of the mid-West. Norman's arranging prowess was further enhanced when the legendary Duke Ellington who had written the standard, praised it as being the best vocal version of the song that he had ever heard.

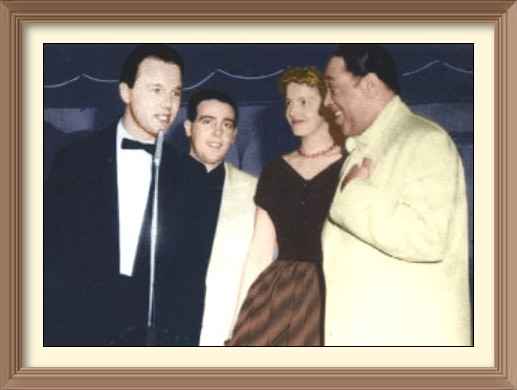

1954: Norman Petty with Jack Vaughn and Vi Petty, pictured

in New York, with "Mood Indigo" composer Duke Ellington

A follow-up "On The Alamo" also made the US Top 40, and over the next eighteen months, the trio scored a number of airplay successes, including "I Wonder Why", "Oh You Pretty Woman" and "Solitude", leading to Cashbox Magazine voting the Trio the "Most Promising Group of 1954" following their first nationwide television broadcast.

Norman Petty had arrived.

Now a successful recording act, Norman got an offer to move the Trio's base to New York and to take up a residency at the prestigious Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue. Although flattered, Norman's affection for Clovis convinced him return home and base himself there, using some of the money from "Mood Indigo" to set up a state of the art recording studio, primarily he recalls, to record the later of the Trio's follow-ups.

Within weeks, he had taken over an empty building adjoining his Dad's garage, and started work on converting it into a fully-fledged recording studio.

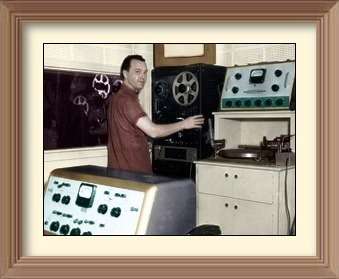

He promptly purchased one of the first Ampex tape machines to be made available outside of the US military, and along with an Altec desk and a professionally-designed acoustic main room, started to produce recordings which enabled the three musicians to sound like a vocal group accompanied by a small orchestra.

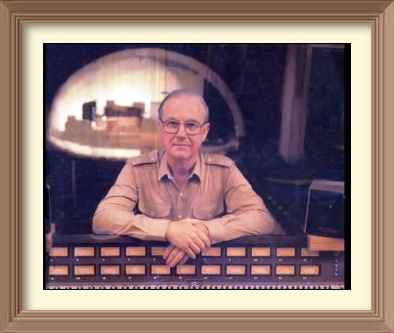

Norman Petty

Norman recalled the original studios:

"The studio itself was around 20 by 22 feet, and the ceilings were about ten foot high. So it was a relatively small room, but we had a large echo chamber that Buddy [Holly], his Dad and his brothers later lined with tile. The studio was very well equipped, but small."

Given that there were already studios in both Albuquerque and Santa Fe, Norman said that he expected to get little if any work from outside acts, nor was he certain that he wanted to.

But the enquiries started to trickle in, and once he began to accept sessions from local bands and singers to supplement the studio's income, Petty decided to offer a fixed price per song, so that no matter how long it took to record the track, the cost to the act would remain the same. This policy he felt, would enable many inexperienced musicians to experiment with the arrangements and produce quality tapes without worrying about money.

When it came to musicians and vocalists, Norman seemed to be blessed with unlimited patience, frequently working eight or ten hours recording just one song. Several singers, such as Buddy Knox, who started out in Clovis before going on to record at major label-owned studios in New York or Nashville, found the relaxed atmosphere in New Mexico to be far more productive.

Norman's drive for constant perfection impressed most people but occasionally irritated a few. Still, it allowed him to boast that nothing left Clovis with his name on it, unless it was as good as it could possibly be.

Although the studio was being used more regularly, cash was still in short supply due to his somewhat unconventional method of charging, so Norman moonlighted as a photographer from time to time, while simultaneously supplying the American Air Force with recorded music programmes made by the Trio.

The rear and garden areas of the Norman Petty Studio, showing the upstairs apartment (left)

The rear and garden areas of the Norman Petty Studio, showing the upstairs apartment (left)

The business was unusual in many ways.

For a start, Norman, who liked to be able to re-arrange tunes during the recording if things were not turning out as planned, hated the clock-watching atmosphere of commercial studios. He particularly disliked the balance on one of the trio's follow-up singles, which he maintained had been ruined by a producer's insistence on cutting short the session when he felt he had an "acceptable" take.

Norman had also been dismayed by a rule in some studios which prevented a producer extending the mandatory three-hour session even by a few minutes, demanding instead that the musicians pay for another full three-hour session to finish off their recording. Now with its own studio, the Trio were free to record what they liked, when they liked. As far as Norman was concerned, the clock was never running.

But then, as he loved repeating: "Creativity doesn't come by the hour".

Another unusual feature of the studios was that Norman himself rarely kept normal business hours, preferring to commence recording sessions late in the evening, and then going through the night. Some of the local musicians also had day jobs, and finding a studio which was not just willing but eager to stay open overnight, was a real bonus.

Anyway, Norman had become used to performing with the trio into the small hours while sleeping during the day, and was convinced that musicians performed best late at night, a view he said was shared by a lot of performers, including Buddy Holly.

There was also a practical reason for this odd scheduling. In spite of Norman's best efforts at sound-proofing, the fact that the studio was situated just a few yards from his Dad's busy workshop combined with the noise from trucks speeding past the building during the daytime, resulted in problems which were difficult to eradicate.

Still, the kitchen attached to the studios was always stocked with the best quality food, and the Pettys enjoyed entertaining the musicians who came to record in the complex. To the side of the kitchen, there was even a spare bedroom where acts could sleep during the day-time before resuming recording again that evening.

The addition of local journalist Norma Jean Berry to NorVaJak as general manager, gave the studios a virtually 24-hour operation. She would open up at 9am, working through the morning until Norman rose, becoming almost one of the family, trusted by the Pettys and well-liked by the musicians who came into contact with her.

Interior Norman Patty Recording Studios, Clovis, New Mexico

Interior Norman Patty Recording Studios, Clovis, New Mexico

Norman's financial arrangements with outside acts were also unusual.

Although Norman quoted a "per-song" rather than a "per-hour" rate, he also offered an alternative deal involving as many free recording sessions as it took followed by his best efforts to place the masters for release, in return for the music publishing on the song, which he in turn would split 50-50 with his co-publishers Peer-Southern Music in New York.

Signing over the publishing was normal in the fifties. Even a decade later, the Beatles would assign their songs to Dick James's Northern Songs while ten years further on again, stars like Elton John were still signing their songs over to publishers, (in his case by coincidence, also Dick James).

Indeed locally, both Buddy Knox and Jimmy Bowen had a similar arrangement with the Texas music publisher Chester Oliver. As Bowen put it: "If he or any of us had any idea what we were doing, he'd probably have ended up a very wealthy man!"

In fact Buddy Holly also had already done a publishing deal in 1956 with Webb Pierce's Cedarwood Music in Nashville when he was recording for Decca prior to meeting Norman - the only difference being that Cedarwood offered him no free recording time. Instead, Decca had billed him $500 for the session!

Petty's business plan, if it could be called a business plan at all, was that each Clovis act which got lucky would compensate the studio for the acts which did not succeed, and hopefully also show a profit. No other studio could have afforded to commence operations on such a basis simply because no bank in its right mind would have advanced money on such a risky premise, but Petty's increasing income from the Trio enabled him to subsidise NorVaJak during the lean years between 1954 and 1958.

In those days, it was seen as a win-win situation for the aspiring star. If he failed, then his attempt at stardom had cost him nothing. If he succeeded, then the backer got recouped through his ownership of the publishing.

Norman's method of financing NorVaJak found favour with no other recording studio:

"I think it's probably a romantic dreamer's way to handle business. Studios today because of the huge cost of equipment, can't do it that way. But we felt we could still make our money and our livelihoods from the copyrights themselves.

We felt that the time we invested in creating copyrights merited spending all the time in the world doing it.

Actually the studio [still] loses money, but it complements the agency type of business we have and the publishing business we have".

Norman Petty at the Norman Petty

Norman Petty at the Norman Petty

Recording Studios, Clovis, New Mexico

Norman also got involved in co-writing, although in years to come, the question of Norman's name appearing as a co-writer on a number of the songs recorded at Clovis would arise.

Norman of course was already a hit composer, but because he penned mainly melodies for the Trio, not many people realised that he was also a skilled lyricist with an excellent command of language. Indeed when he had enrolled at the Eastern New Mexico University in Portales just after his military service, his preferred discipline was Speech & Drama.

Bill Pickering of the Picks, who later provided the harmony backgrounds to The Crickets' hits, remembers asking Norman in the middle of a recording session if they might at some stage record the Petty instrumental "Moondreams" - but as a vocal. Norman suggested that then was as good a time as any to do it, and as Bill recalled - "he wrote the lyrics for that in about thirty minutes just before we sang it"!

As for the suggestion that Norman Petty simply added his name to Buddy Holly's songs, who better to ask than Buddy Holly himself, who in a 1958 interview said:

"Our aim is to concentrate on original material and to produce a distinctive sound of our own. Between us, Norman and I have written quite a lot of songs, and we hope to open our own music publishing house some time in the near future."

But no matter how advanced his songwriting skills were, Norman ended up being credited as a co-writer not only on the many songs to which he had contributed, but also on songs to which it could be argued he had added little if anything of any great significance, apart from changing perhaps the arrangement, or suggesting some extra lyrics.

Having said that, it should be noted that even his "minor" contributions probably made all the difference, such as showing Sonny West and Bill Tilghman how to re-write a a love song their lyric penned about a domestic brawl between two lovers, while keeping the same title - "Rave On"!

Or indeed again, when he advised the same writers to change the somewhat pedantic title of "All My Love" to the more with-it "Oh Boy" although to be fair, in that case, he also re-wrote much of the lyrics as well.

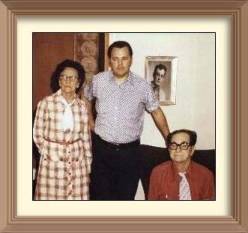

Bill Griggs, pictured with Buddy Holly's Parents

Bill Griggs, pictured with Buddy Holly's Parents

[Photo Courtesy Bill Griggs]

The noted writer and Holly expert Bill Griggs who investigated the question of song credits, and who has had total access to all the files and correspondence at Clovis, wrote the following in a letter to the International Songwriters Association:

"The only things I had to go on about Norman Petty were [stories] I had been told by others. While doing research for the BHMS, I started meeting more and more entertainers that Norman had originally recorded in Clovis, and they all told me the basically the same thing. Norman said to them: "I'll put my name on the song along with yours. If it is a hit, we all make money. If it fails, I'll take the loss".

For years, I had really hated Norman Petty. Then as time went by, I learned more and more at first hand about the dealing in Clovis and I found that most of the stories [I had been told] were simply not true."

Consequently, Norman was clearly upset by later criticisms of this deal. To him, it had been a straightforward business arrangement with songwriters who were free to accept or reject it, and he clearly saw nothing untoward in it.

Songwriter Jim Robinson, a first cousin incidentally of country star Johnny Horton, who worked with Buddy Holly and Norman Petty and went on to write hits for Charlie Pride, Waylon Jennings and Red Foley, told Bill Griggs:

"Of course Petty was involved in some of the writing as far as his name on the song is concerned. You know there wasn't that much money back then...but Petty would make a deal. We'd go up there and record and he wouldn't charge us any money for the studio use.

He more or less would say: "OK, I'm going to put out my time and effort and you're going to put out your time and effort, and we'll split this thing down the middle", which was a very good situation. He got a lot of boys started that way, I know he did.

If I wrote a song, he'd look it over and maybe change a couple of words, and I'd put Petty's name on it too. Well that was all right too, it got my name exposed and it helped me get my foot in the door....Norman was a very very quiet man, a definite perfectionist. I know that he liked to work me to death. Once we did twelve hours on one song!"

The charges got their first airing in John Goldrosen's book "Buddy Holly", although as Bill Griggs told me:

"I can assure you that John Goldrosen was not looking for [to do] a hatchet job on Mr. Petty. When John went back to Petty while the book was being rewritten, Norman Petty really didn't defend himself".

Bemused by his apparent indifference to criticisms, a number of former Clovis acts started coming forward in Norman's defence realising that however fair they might feel he had been in his dealings with them, his failure to answer his critics now cast him in a very bad light. Some of those who supported Norman even pointed to the fact that he had often not taken co-writer credits on songs which he had actually co-written with them.

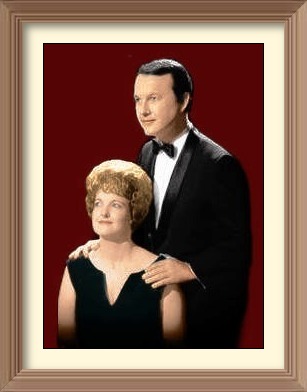

One of the more relevant contributions came from a friend of Buddy Holly's, who with his wife Ramona, had been one of the background singers on "That'll Be The Day".

Gary & Ramona Tollett

Gary & Ramona Tollett

Like Buddy, Gary Tollett was hoping for a recording career, but unlike Holly, and in spite of having a number of songs recorded by Norman on which Buddy and members of The Crickets played guitar, he failed to make his own breakthrough.

His opinion of Norman Petty many years later?

"Norman was a quiet, determined gentleman, always businesslike, very polite. I never had one minute's trouble with him as far as him trying to give me a hard time when working in the studio, or him trying to get me to do something I did not want to do. He offered suggestions at times, it was his studio, but he never charged me a penny for all the hours I spent in there recording myself.

He was an absolute gentleman. I think the world of Norman and I think he was badly misjudged by a lot of people saying he took more of Buddy's earnings than he should have. From what I knew, he always did what he said he would do.

He was a gentleman, who let us use his studio and wouldn't charge for it. He worked hard, he worked all through the night with us when we were doing things, offering suggestions, and all sorts of things. I always felt good towards Norman Petty and still do".

Vi Petty later explained her husband's reticence as follows:

"I remember Norman doing so many songs for so many people and changing their words or melodies and never even putting his name on the song. Norman believed that in the end, the truth would come out, and that was all that mattered".

But as Norman ruefully, and more realistically remarked to me:

"Once the allegations are made, there is little to be gained by arguing figures with people who have already made up their minds".

Still, the opinion of Buddy's brother, Larry Holly, from many years later, is worth mentioning:

"Regardless of what anyone says, Norman was responsible for getting Buddy out. Buddy knocked at the doors in Nashville and several other places, but when he got with Norman, that's when it all started for him. He is a genius. He is a likeable guy, and very fair. I like him".

NorVaJak Complex, Clovis

Norman's new business, the strangely-named NorVaJak, comprised a studio and a tiny custom record label which could arrange the supply of whatever vinyl records an act might want, with the pressings usually carried out

at a plant in Phoenix, Arizona.

"We called the company NorVaJak, making up the name from Norman, Violet Ann and Jack who played guitar with the Trio, but we built the studio for our own use.

None of us appreciated the pressure a musician is under in a commercial studio where you keep watching the clock and realise that every extra minute you take is costing you money.

Anyway, we never really advertised the studio at all, but naturally word got out that there was this studio in Clovis with excellent equipment and people started coming in and asking us to record them".

It was indeed excellent equipment, and Norman had also developed his own state-of-the art echo chamber in the loft over his Dad's garage (part-tiled incidentally by the Holly family's tiling business) which produced a beautiful reverb sound. At one stage, even Henry Mancini was sending over to Clovis masters of his orchestra so that they could be processed through Norman's system.

The ancillary equipment at the tiny complex (much of it self-built), coupled with Norman's unerring engineering skills, produced a sound, which disguised the tiny number of musicians actually involved. His skill at "doubling", "double-tracking" or "pinging", which in the days prior to multi-track machines involved a complex "bouncing" of one machine off the other, was such that virtually no sound degradation was noticeable.

The studio also boasted a Baldwin grand piano (tuned regularly by Norman himself), a Hammond organ, a 50-year old Swiss Celeste, a Telefunken 47 for vocals, a Stevens pencil microphone or an RCA770 for the bass, and an Electro-Voice 635 on the guitar amplifiers.

Norman Petty Studio

But it was the total attention to detail, from the placement of the microphones to the cutting of the acetates, which really set the studios apart. Norman for example, even built a tiny AM transmitter enabling him to put an acetate on a repeating turntable in his studio, then drive around for a few blocks listening to it on his car radio! That way he said, he could gauge what the record would sound like to teenagers hearing the song for the first time (as most did), in their cars.

Norman never lost his interest in innovation. Every new idea, every new instrument, every new style of music (even when he did not much like it), was fascinating to him. When he set up the first FM station in Clovis in 1961 for example, recalling his own gaffes as a teenage DJ on KICA, he immediately built a home-made analogue computer to remove the gaps between the tracks on LP records, so that an entire album could be played without any dead-air between the songs.

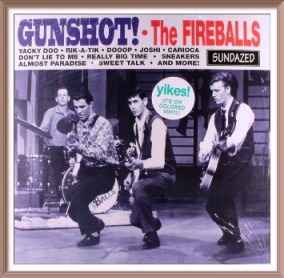

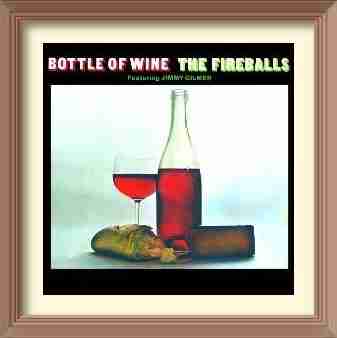

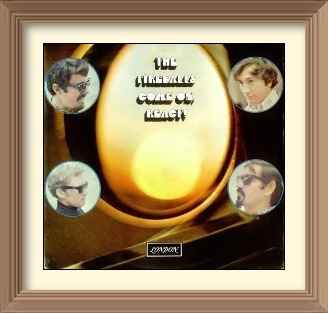

What also made the Clovis operation so unusual was that the owner was also an accomplished musician. He played the funky piano on "Rave On" for example, the beautiful celeste on "Everyday" (although he gave the credit for that to Vi who taught him the part), and the catchy Vox Organ riff on "Sugar Shack" which turned a fairly ordinary song into the biggest selling record of 1963 (and for which incidentally he did not take any writer's credit).

Norman rarely interfered, but he was always happy to give advice.

And of course, he was blessed since childhood with that most treasured of musical gifts, "perfect pitch" as many guitarists found out to their cost when a take had to be scrapped because Norman had heard an "off" note which nobody else could hear!

Norman Petty at the desk

of this studios in Clovis, New Mexico

In reality, Norman was undoubtedly more at ease around musicians than anybody else, and this helped create a relaxed atmosphere for those recording in Clovis. And in spite of his own stated preference for what her termed "beautiful" music, he was certainly no musical snob. From rock to jazz, from country to Mexican, from folk to psychedelia, Norman recorded it all.

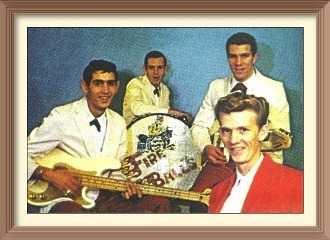

One of the earliest acts into the revamped studio were Roy Orbison and The Teen Kings, comprising James Marrow, Jack Kennelly, Billy Pat Ellis, and Johnny “Peanuts” Wilson. The band had been signed to the newly-formed Jewel label, owned by Weldon Rogers and Blue Moon Music publisher Chester Oliver, a local Phillips Petroleum executive and friend of Norman, who operated out of Seminole, Texas. The band cut "'Ooby Dooby' coupled with "Trying To Get To You" at Clovis in March 1956.

The record took off in Texas, but legendary producer Sam Phillips, informed by a record store owner that Orbison might have been under 18 when he signed the contract (which would make the agreement invalid), moved quickly and with Roy Orbison's father's signature, signed the young singer to his own Sun Records in Memphis.

The re-cut version of "Ooby Dooby" reached the US Top 60 the following year. Chester Oliver, who saw his original investment going down the drain, appealed to Norman, who quietly purchased an extra 5,000 copies of the disk from a pressing plant in Phoenix, Arizona, to help Chester recoup his money.

Roy Orbison

But it was The Rhythm Orchids, comprising Buddy Knox (from Happy, Texas) and Jimmy Bowen (from Santa Rita, New Mexico), who lifted Norman into the national industry consciousness when they recorded two songs at the Petty studios in late 1956.

Jimmy Bowen, in spite of a self-effacing persona, turned out to be anything but a minor talent. He would go on a few years later as a producer for Reprise Records, to save both the label and the declining careers of Dean Martin (with "Everybody Loves Somebody" and later "The Door Is Still Open To My Life" and "Houston") and Frank Sinatra (with "Softly As I Leave You" and later "Strangers In The Night" and "That's Life"), before eventually becoming one of the greatest producers and label bosses country music has known or probably ever will, scoring no less than 70 Number Ones, guiding the careers of Garth Brooks, Merle Haggard, Reba McEntire, George Strait, Conway Twitty and Hank Williams Jr.

He described the Norman Petty session in what is pme pf the best books ever penned about music production - "Rough Mix" [published by Simon & Schuster].

Bowen recalled that the Clovis operation comprised only "a tiny one-room studio, and control room, at the end of his apartment complex", adding however that "Petty seemed to know what he was doing".

At the end, Jimmy paid over $300 cash for what he described as "studio time and for his extraordinary patience as engineer and producer" adding that Norman had spent eight hours to get just one side "out of four half-assed musicians".

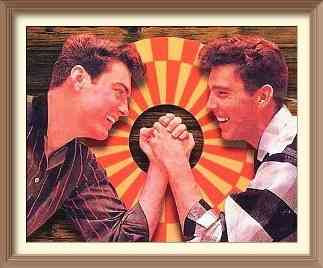

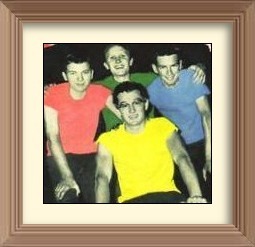

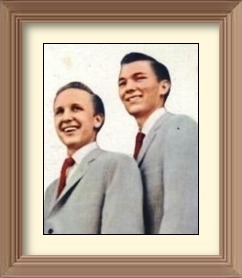

Jimmy Bowen & Buddy Knox

Chester Oliver ended up paying for that session as Norman meanwhile was having second thoughts about pressing the single on NorVaJak.

Throughout his life, Petty remained a member of the Central Baptist Church in Clovis, a religious man who advised all of his acts to carry a bible with them on tour and forbade alcohol and cigarettes (and even swearing) within the studio complex. He was initially interested in "Party Doll", a song which he had spent many hours recording, until he listened more closely to the lyrics. Upset by the line "and I'll make love to you", Norman declined to release the song on NorVaJak.

Chester Oliver on the other hand, was happy to finance the setting up of a one-off label for the band, Triple D Records (named after radio station KDDD in Dumas, Texas), to release the two tracks to radio.

"Party Doll" on Triple D

"Our first really big record from the studio, in 1956 - "Party Doll" sung by Buddy Knox, and of course, we also had a hit with Jimmy Bowen's "I'm Sticking By You". Buddy Knox and Jimmy Bowen along with a friend of theirs named Donny Lanier, came over to the studio one day.

They wanted to put out a record to sell at high-school hops, and so for sheer economics, instead of doing two separate records, they decided to put out one disc with one singer on one side, and one on the other.

Later on of course, Roulette Records who picked up the rights to the recordings for national distribution, split the record, and the two sides went on to become two separate million-sellers".

A year on, now a star signed to Roulette Records and being produced by the top New York producers, Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore, Jimmy Bowen had this to say:

"Despite the know-how, fancy equipment and big-city egos, Hugo and Luigi failed to draw out of us the raw magic that Petty had captured in Clovis. We should have insisted on going back..."

As a result of the publicity which followed this double-hit (both made the US Top 20 with "Party Doll" reaching Number 1), the studios began to attract singers and instrumentalists from further afield. In addition, Petty himself, seen up to now as primarily an instrumentalist and composer, was getting noticed in New York as a producer.

The major labels watched Norman's progress in much the same way as they kept a track on Sam Phillips in Memphis, and doors previously closed to him, soon began to open. It might have seemed like a compliment, but it was rarely a blessing. Having failed to latch on to rock and roll at its birth, many of the labels were now desperately trying steal, poach or purchase what talent they could from regional producers.

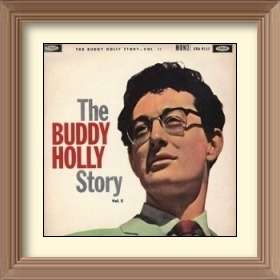

Meanwhile, Clovis bean to attract other hopefuls but now from neighbouring Texas - people like Trini Lopez from Dallas, and in December 1956, Buddy Holly from Lubbock.

Buddy Holly was just 20 years old, a warm-hearted, likeable, good-natured and generous person, whose family (the Holleys) operated a tiling business in Lubbock. His father was a good-humoured hard-working man and probably Buddy's greatest fan and Norman who got to know the family well, describes Lawrence Holley as "the real father of the Crickets".

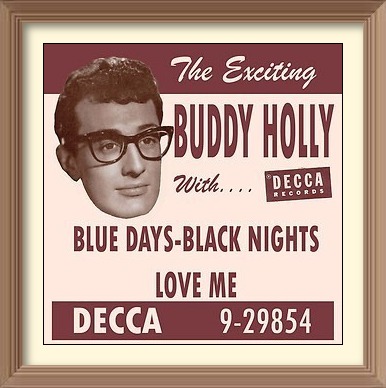

Buddy Holly was not new to the recording scene, nor indeed to Norman Petty. A year earlier, he had recorded eight song demos at Clovis, subsequently cutting two semi-country singles for Decca Records in Nashville, "Blue Days, Black Nights" and "Modern Don Juan", but those singles had failed to chart and Decca had hinted that they might not exercise a renewal option in his contract in January 1957.

Buddy Holly

Undeterred but not willing to wait around to find out what Decca would do, Buddy drove the 90 miles back to Clovis to see what his next move should be.

Petty talked with him for a while, and then suggested that Buddy should go back to Lubbock, put together a band to rehearse two original songs, before returning to Clovis.

Norman told me simply that he took an "immediate liking to Buddy from the very first moment" they met, although in an earlier interview with journalist Norman Mark, he had delivered a possibly more pragmatic response:

"My first impression of him was of a person ultra-eager to succeed. He wore a T-shirt and Levis. Really he was unimpressive to look at but impressive to hear. In fact businessmen around here asked me why I was interested in a hillbilly like Holly, and I told them I thought Buddy was a diamond in the rough".

According to Norman, Buddy got on well on a personal level with both himself and Vi, often driving over to Clovis to hang around the studios, sitting in on some sessions, trying to learn more about the recording process and picking up anything he could about how the music business worked. In turn, Norman found Buddy to be "respectful" and "responsible".

And even though Norman did not necessarily understand rock and roll, he liked it (although Vi did not), and above all, he appreciated Holly's talent:

"I didn't know if I was going to be able to understand what he was trying to do and I have been criticised for not really understanding, but I think that we pretty well respected each other's capabilities. It was a nice chemistry thing for both of us, I think."

When lauded later for having created Holly's style, Norman was dismissive:

"Not so. I was able to capture or accentuate the peculiar things he did as an artist but I was no magician where Buddy was concerned. You don't create talent - it's there".

Norman in fact has never claimed to be able to "make" somebody a success:

"I have tried to become an astute observer of seeing what an artist does well and then polishing it. Being a good listener and transferring what I hear onto tape".

Buddy Holly

Buddy appeared back in Clovis on the 24th February 1957 with drummer Jerry Allison who had accompanied him to Nashville, Larry Welborn (from Lubbock but born in Oklahoma) on bass, rhythm guitarist Niki Sullivan (also from Lubbock but a native of California) who however only came along this time to sing background, and an ad-hoc vocal backing trio made up of Lubbock residents Gary and Ramona Tollett and June Clark.

After a session lasting from around 9pm and ending at 3am the following morning, Norman delivered two tracks, a somewhat hurriedly-penned "I'm Looking For Someone To Love" which oddly, given that the date had been planned for several weeks beforehand Buddy had still not finished and to which Norman had to contribute some last-minute additions, and a remake of an unreleased Decca Nashville song titled "That'll Be The Day".

Although the quality of both sides was acceptable, Norman would have continued for longer except that two of the party had to get back to Lubbock before breakfast.

Petty felt that there were some rough patches on "That'll Be The Day", particularly what he heard as an "off" bass note coupled with some ragged playing towards the end. However, Buddy had assured him that these were merely demos, to be played to a contact he had in New York.

Although Norman did not know then who this contact was, he guessed that it was somebody in the Rhythm Orchids. In fact that could very well have been the end of the connection between Buddy and Norman but within two weeks, Buddy was black in Clovis.

It turned out that the contact Buddy had been hoping to place the demo with was Teddy Lanier, a New York shoe model and a social friend of Roulette Records boss Morris Levy. Levy had recently formed the label which in later years would boast such names as Pearl Bailey, Count Basie, Lou Christie, Dave "Baby" Cortez, Sammy Davis, Jr., Joey Dee and the Starliters, Duane Eddy, The Essex, Ronnie Hawkins, Tommy James & the Shondells, Frankie Lymon, Jimmie Rodgers, The Three Degrees, Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington.

Jimmy Bowen

Teddy Lanier also just happened to be the sister of Buddy Knox's rhythm guitarist Donny Lanier and had already helped to place both Buddy Knox and Jimmy Bowen on Roulette, assuring Donny that she could place Holly as well.

However, even though he was aware that it had been produced by the same person that had given him "Party Doll", Morris Levy turned down the demo although his partner Phil Khals, who ran the publishing side of the operation, showed an interest in having Buddy Knox record "That'll Be The Day" with Donny Lanier perhaps cutting "I'm Looking For Someone To Love". When Lanier told Holly this , Buddy rushed back to Clovis and asked Norman if he could get involved in placing the record.

Norman had always viewed "That'll Be The Day" as the stronger song, and now decided that the best way forward was to re-assemble the group and do a new recording of the tune, up to master quality standard. He did not fancy the idea of taking what he regarded as a flawed demo to his strongest New York contact, Mitch Miller at Columbia Records.

Up to now, Petty had known nothing about Buddy's previous contractual arrangements. He did not know (nor was he to learn now either) that Holly's Decca recording contract actually forbade him from recording for five years, any song which had been laid down in Nashville even if Decca had not released it. This of course included the unreleased "That'll Be The Day".

Buddy however did mention to Norman that Cedarwood Music in Nashville had presented him with a publishing contract for "That'll Be The Day", but that he had failed to return the signed copy. This at least looked promising, but in fact when Petty did a search, he discovered that contract or no contract, Cedarwood had in fact gone ahead anyway and registered "That'll Be The Day" as one of their copyrights.

Buddy might not have understood the full implications of this, but Norman most certainly did.

If Roulette did the same search he had just done, they would also discover that the song had been assigned, meaning that they could simply license the tune directly from Cedarwood without obtaining Holly's prior consent.

Secondly, although Norman's usual terms were that the publishing would be his if he placed an act with a label, he now discovered that the publishing of "That'll Be The Day" was already given to Cedarwood anyway.

Accordingly, and realising that time was now of the essence, Norman told Buddy that he would add his own name on the song as co-writer and then promote it as a demo to his contacts in New York. This was readily accepted by Holly.

[It should be added that Jerry Allison, who penned the song along with Buddy, has stated that he was not happy with this arrangement].

Norman immediately flew to New York where he already kept an apartment at West 57th Street. His first port of call was to Mitch Miller, head of A&R at both Columbia and Mercury Records and himself a hugely successful recording act whose musical tastes were quite similar to Norman's and whom Petty regarded as a friend.

Miller, like most producers working for the larger labels, was coming under increasing pressure to sign some rock and roll acts but with no great liking for what he regarded as a vulgar and fleeting musical trend, Miller was depending on a small number of "associate producers" of which Norman was now one, to come up with the goods for him.

Mitch Miller

According to Norman however, the early-morning meeting which started out as a friendly chat, quickly turned into a total disaster. Miller made it clear that he was disappointed with both the songs and the act, advising Norman to drop the project, adding that there was no point in persisting because he was certain that no other New York label would sign them either.

Norman had been so confident of his relationship with Mitch that he had made no other appointments. He tried to arrange a lunch meeting with Jerry Wexler at Atlantic Records whom he had never met but with whom he had corresponded, but was unable to set it up at such short notice.

Instead, he decided to drop in on Murray Deutch at Peer-Southern Music, the company which at that time was co-publishing Norman's own compositions as well as administering the newly-launched NorVaJak Music nationally. It was partly a social call as Norman recalls, and partly in the hope that Murray could recommend somebody else to approach.

Deutch was a good-humoured veteran of the New York publishing industry, with strong ties to Decca Records. They had not met before although they had spoken frequently by telephone, and after some small talk, Norman explained to Deutch what he was doing in New York.

Murray was annoyed that Petty had not come to him first, a view he was to repeat frequently in later years, but he loved the record and offered to help promote it on condition that Southern Music could have half the publishing on both sides if he got one of his contacts to offer a deal.

The Cedarwood problem was the very reason Norman had not bothered to approach Southern in the first place, but hoping that he might be able to wrest control of the publishing of "That'll Be The Day" from Cedarwood on the basis of their non-returned contract, Norman agreed.

Murray phoned several people that afternoon, but none were available to meet or were simply not interested. Eventually, he got an appointment with Coral Records.

The pair walked over to the offices of Coral (a Decca subsidiary) and Murray introduced Norman to Coral's Head of A&R, producer Bob Thiele, husband of Coral's big star Teresa Brewer, a former independent producer, label owner, and a jazz buff who many years later would co-write the classic "What A Wonderful World" for Louis Armstrong.

Bob Thiele

The choice was unusual, and Norman felt that it smacked of desperation on Murray's part. Bob Thiele was best known for his jazz productions while Coral was not a label regarded as sympathetic to rock and roll. Its parent company had achieved massive international success with Bill Haley, still at the peak of his career, but its subsidiary Coral in its early attempts to emulate Decca's achievement, had failed disastrously in its forays into the new market.

Norman went ahead anyway, explaining yet again that what he had was just a demo which he would of course be happy to re-record for Coral before release.

To Petty's surprise, Thiele dismissed this offer saying that he liked them as they stood and was prepared to do a deal for the tracks, suggesting an relatively small advance but sweetening it with a higher than usual royalty. Norman, running out of time and options, quickly accepted the offer.

As Norman said:

"Bob was the hero because up to that moment, I was already on my way back to Clovis to re-record it".

The deal on offer was not as good as Norman had hoped for or had obtained for his own Trio from Columbia. Also, he had heard that Buddy Knox and Jimmy Bowen had reputedly negotiated a $3000 advance for the masters of "Party Doll" and "Sticking By You" so that even after they had paid over 50% to Chester Oliver, they were still $1500 to the better.

In fact, low advances may simply have been Coral's usual opening gambit. One year later and at the height of his fame, Buddy himself fared little better. In November 1958, when he produced his first master - Lou Giordano's "Stay Close To Me" - Coral took it, but offered an advance of just $350.00.

Lou Giordano

In any event, the inability of Norman to hold out for a better deal helps put into perspective the disputes which arose later. At a time when the general public was convinced that every rock and roll singer was at least a millionaire, the four members of The Crickets only ever stood to collect $40,000 between them in mechanical royalties should the single go on to sell a million copies.

Not too many musicians in those days did the maths, although there seemed to be a theory at large that if you sold a million records, then you ended up with a million dollars. In fact records sold in shops for between just sixty-nine and eighty-nine cents each, while the royalty was often as low as one cent per side.

Buddy himself was of course would have been aware of this. His first royalty statement from Decca Nashville in June 1956 showed that having sold just under 10,000 copies of "Blue Days Black Nights", he had earned a grand total of $113.77! (Not that he even got this pittance from Decca who had added a charge of $500 for the recording session, meaning that he would not get his first cent in royalties until he had earned another $385.97 for the label.)

But although Norman and Buddy might know the score, those around Holly may well not have. Niki Sullivan for example said later that he had been expecting "hundreds of thousands of dollars" from the one single "That'll Be The Day", whereas under the terms of the royalty from Brunswick (not to mention the band's own internal split of 60% for Buddy with the remaining 40% divided between the other members), Niki's entitlement was never going to be much more than a tiny fraction of what he honestly believed it should be.

Norman Petty Trio 1955

Meanwhile, there were other matters to be ironed out. The act was now performing around West Texas minus the original backing vocalists but with a new bass player Joe B Mauldin, as "Buddy Holly & The Crickets", but Decca Nashville had still not officially released Holly from his contract with them. More ominously, Norman had since learned that Decca's usual contract forbade a singer from re-recording anything he had already recorded for them, for a five-year period.

Although Norman viewed this as purely an internal matter to be resolved by Decca HQ who after all owned both Decca Nashville and Coral, Thiele did not want to risk a delay, and so he and Petty agreed to kick that particular problem down the road by leaving Buddy's name off both the record and the contract, releasing the tunes instead under the collective name of "The Crickets".

"Buddy Holly & The Crickets" 1957

Murray Deutch who had made the crucial introduction, was now looking for his share of the publishing so Petty decided to try a personal approach to Jim Denny, manager of Cedarwood.

Following two inconclusive phone calls, Petty finally flew to Nashville, met with Denny, and eventually persuaded him to hand over the song to NorVaJak so that Norman could share it 50-50 with Southern Music. It was after all he argued, only going to be a "B" side anyway, of a song which Decca had not even bothered to release. He also suggested that Cedarwood might not have a contract at all and that a legal battle on the basis of there being an implied performance agreement, could be a long and costly affair.

In the end, Denny reluctantly agreed, but only after extracting a guarantee that Petty would give Cedarwood a future Crickets' release.

Soon after Norman arrived back in Clovis however, Murray Deutch phoned with the news that in spite of Thiele's enthusiasm, Leonard Schneider at Coral had baulked at issuing "That'll Be The Day" on a label which already featured such upmarket acts as The McGuire Sisters, Pete Fountain, Lawrence Welk, Steve Allen and Debbie Reynolds, on the grounds that the "raucous music" of The Crickets would damage the image of Coral Records. In retrospect this seems unlikely, the label having already released the Johnny Burnette Trio amongst others.

However, according to Deutch, Thiele had kept fighting for the song, and Coral had finally agreed to let him put the track out on Brunswick, a label which had been revived in 1952 to release mainly rhythm and blues acts.

Brunswick was a less prestigious label than Coral, and Norman was bemused by the apparent change of heart, even more so when a few weeks later, Thiele, having heard Buddy's song "Words Of Love", had no trouble negotiating a solo contract for Buddy with Coral.

[It probably did little harm that the flip side was to be a Thiele number, "Mailman Bring Me No More Blues", co-written by the producer under a pseudonym].

Back in Clovis, Norman brought the band over to Clovis to break the good news that The Crickets would be shortly appearing on Brunswick, Buddy Holly would be out on Coral, and that they were all welcome to return to Clovis as often they wished, to record as much as they liked.

Even though nothing had yet emerged from New York and Norman had no way of knowing if what did emerge would be successful or not, Petty now devoted hundreds of hours to the band, recording the bulk of the material which would dominate the American charts over the next eighteen months, including such classics as "Peggy Sue", "Oh Boy", "Listen To Me" and "Words Of Love".

It is doubtful if any record producer had ever invested so much time in an untried act, as did Norman Petty with the Crickets.

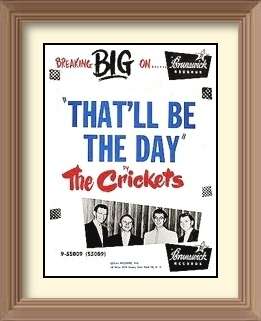

Finally, after what must have seemed a lifetime to the young musicians from Lubbock, the Crickets "That'll Be The Day" emerged on Brunswick in May 1957, followed two week's later by Buddy Holly's "Words Of Love" on Coral.

"That'll Be The Day" by The Crickets was a slow burner, but finally reached Number 1 on the US Hot 100 in September, spending no less than 23 weeks on the chart.

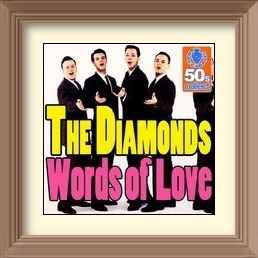

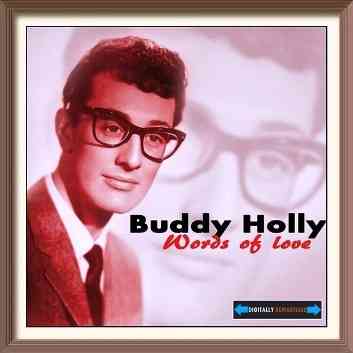

Disappointingly for Norman, Buddy's single failed to reach the Hot 100 at all, although a cover version of "Words Of Love" by The Diamonds, given to them by Murray Deutch who had seemingly not shared Norman's confidence in Holly's own version, did make the Top 10, earning Buddy his first royalty cheque as a songwriter.

"Words Of Love" The Diamonds and "Words Of Love" Buddy Holly

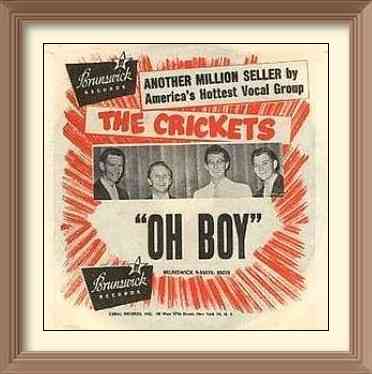

However, the disappointment would have been short-lived anyway. Thirteen weeks later, Buddy's follow-up "Peggy Sue" reached Number 3 on the Hot 100, and with the new Crickets record "Oh Boy" also racing up the charts, Buddy Holly & The Crickets had come from nowhere to become one of the hottest recording acts in America, scoring a Gold Disc each.

And Norman Petty - the musician whose idea of seriously energetic dance music was the Glenn Miller Orchestra playing "In The Mood" - had emerged somewhat to his own surprise, as one of the hottest producers on the rock and roll scene.

Although The Crickets and Buddy Holly were legally two distinct recording acts on two different labels, the reality was that Buddy was the lead singer on every single record. However, as Norman had arranged two separate recording contracts (a ploy later used by Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons), Buddy Holly or The Crickets were able to make no fewer than nine appearances in the American charts in the eighteen months between September 1957 and March 1959.

The records by the Crickets always made use of vocal backings (dubbed on afterwards by Norman using two local vocal groups, The Picks or The Roses) and were generally more rock-orientated. Those by Holly were regarded as being more progressive and "sweeter", and (until Bob Thiele insisted on putting a male harmony backing on "Rave On"), lacked vocal accompaniment. The most distinctive thing however about both sets of releases, was the unusual and immediately recognisable sound.

The Crickets. Buddy Holly, Joe Mauldin,

Jerry Allison and Niki Sullivan:

New York City 1957

Did Norman consciously develop one sound for Buddy Holly, and a different one for The Crickets?

"No. I felt our sound was special. Some have said it was the guitar sound, while others have felt that the drum sounds from the studio were unique.

However, the "sounds" used on the different songs usually "caused" one song or the other, to be designated as a record for release under the name "Buddy Holly" or under the name "The Crickets".

We did not consciously decide these things in advance".

As 1957 ended, "That'll Be The Day" had sold over a million copies, and Buddy Holly's own solo career was blossoming with "Peggy Sue" in the US Top Ten. The Crickets follow-up "Oh Boy" had got great reviews and was soon racing up the US charts.

Norman Petty was also a busy man, Holly having asked him to act as the outfit's personal manager after "That'll Be The Day" started to break in July 1957.

Norman was not keen to manage anybody, and certainly not if it involved leaving Clovis for any length of time or abandoning his beloved Trio which was again experiencing national success, this time with "Almost Paradise". In any event, Mitch Miller, having snatched the Trio away from ABC-Paramount and appointed Norman as an Associate Producer at Columbia, was now demanding an album which would take some weeks to record.

Norman Petty Trio 1957

In addition, the Clovis studio was heavily booked into the immediate future. As Tommy Allsup, who worked for Norman as a session guitarist recalled: "I did a different session every single night. Petty had them lined up at the door".

Instead of pointing out the obvious, namely that he knew nothing about rock and roll management and that in any event, the Crickets would be better served if he was taking care of business back in Clovis, Norman merely suggested that he would prefer not to get involved, citing only that he would be unable to travel with the act as managers usually did.

For some reason, The Crickets persisted, and finally Norman accepted, offering however to take just the agent's fee of 10% instead of the more usual 25% or 50% (Brian Epstein or Colonel Tom Parker) most rock era managers took of their client's earnings.

Significantly, Norman offered no management contract, thus leaving either side free to walk away any time they wished.

Becoming manager was a decision Norman regretted:

"I was concerned with the boys' personal well-being as well as their professional well-being. Also I was probably a little too restrictive. Jerry Allison has voiced his opinion that I was a little too domineering [and] dominated the whole group, but I really didn't try to do that.

It was more or less a family situation, not a father and son [situation], but everybody pulling for each other as far as I was concerned. I'm sure I made mistakes but they were all mistakes made in an effort to do what I thought was best for the whole group".

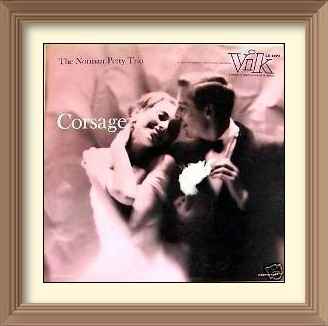

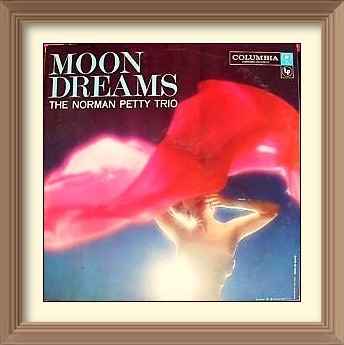

Various Norman Petty Trio releases including

Various Norman Petty Trio releases including

"A Petty For Your Thoughts", "Corsage" and "Moondreams"

Meanwhile, Norman had again made waves with his own Trio and its "beautiful" music.

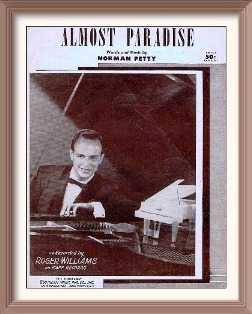

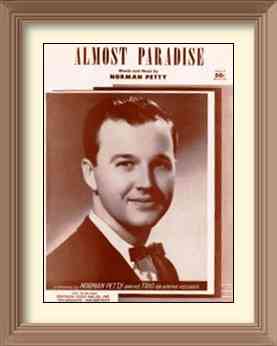

His latest composition "Almost Paradise" published by Southern Music, and recorded by the Norman Petty Trio on ABC-Paramount had been released in January 1957, entering the charts four weeks later, bound it seemed for the Top 10.

However, Southern Music now promoted the song to other pianists, and almost immediately, two cover versions appeared. The first on Kapp Records was by Roger Williams, one of the most successful piano stars of the 20th century, whose "Autumn Leaves" had reached Number 1 on the Hot 100 eighteen months earlier earning him (and Kapp Records) their first Gold Disc.

The second was by the New York session musician, Lou Stein, on RKO Unique.

Far from being pleased by these prestigious cover versions, Norman watched horrified as all three recordings raced into the Top 50 with the version by Roger Williams passing out Norman's, reaching the Top 10 in March.

Norman told me that he could not understand why Murray Deutch of Southern was congratulating himself on obtaining several cover versions which in Petty's view had prevented the Trio from topping the charts, and Norman from getting a substantial and much-needed royalty.

The fact was that Norman had not been in receipt of songwriting royalties prior to this as the Trio's previous hits had all been cover versions. Accordingly, as he sheepishly remarked, he had no idea that composers got the same royalties from cover versions of their compositions as they did from their own version until Murray explained it to him.

In spite of the royalties, Murray's "achievement" remained an irritant with Norman, and was exacerbated when Deutch similarly promoted Buddy Holly's first single "Words Of Love" to The Diamonds, enabling them, and not Buddy, to make the US Top 10 with his own song.

Still there were lots of cover versions of "Almost Paradise". Almost immediately, the song was covered by trumpeter Eddie Calvert amongst others, eventually amassing total sales via all versions of over one million copies, and Norman's first very substantial royalty cheque.

"Almost Paradise" opened Norman's eyes to a mysterious world centred in New York - the world of music publishing, and after what he described as a "crash-course in music publishing from Murray Deutch", he promptly formed NorVaJak into a music publishing outlet, to be administered by Peer-Southern on a 50-50 basis.

Roger Williams met Norman Petty later that year at the annual BMI Awards. By now, Williams had released an LP with "Almost Paradise" as the title track, and it was being featured on thousands of radio stations worldwide.

The pair chatted quietly together after the banquet, and as Williams later said, he found Norman to be a very knowledgeable musician and a wonderful composer, adding "the tunes he wrote were simply beautiful".

Norman had consequently, and for the first time in his life, become financially secure, and Mitch Miller, one of America's most influential record producers and Head of A&R at Columbia promptly signed the Trio to the prestigious label with their first release "The Last Kiss" becoming one of BMI's most played tunes of 1957.

"Almost Paradise" Norman Petty's first million selling composition

which was a hit for both Roger Williams and the Norman Petty Trio

In addition, more diverse acts in the country and even folk music fields, were taking advantage of what 1313 West 7th Street, Clovis, had to offer.

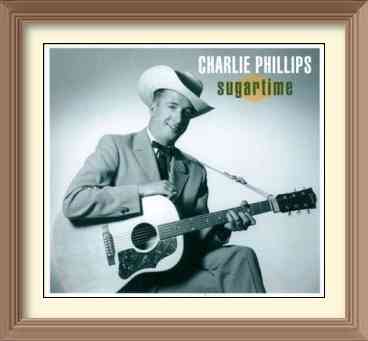

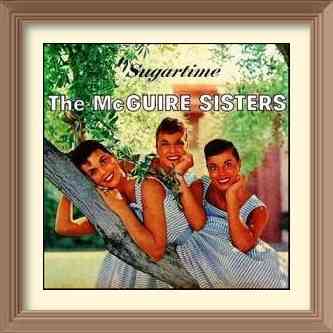

Charlie Phillips from Clovis brought "Sugartime" to Norman in 1957, a song co-written with influential broadcaster Odis Echols who owned KCLV radio station in Clovis, and who would later serve in the New Mexico State Senate between 1966 and 1977.

Petty liked the tune, and set up a session featuring Buddy Holly on guitar, Jack Vaughn on acoustic guitar, Jerry Allison on drums, Jimmy Blakely on steel guitar and George Atwood on bass. The record, with overdubbing by the Roses, was sent to Coral in New York who released it to the country market where it became an immediate hit in Texas and New Mexico, selling according to Phillips, in excess of 450,000 copies.

Norman suggested that Coral should also give it a pop treatment using the female vocal group The McGuire Sisters. Petty was on a roll at that moment, and so Coral listened, unusually, to outside advice. The pop version raced up the Hot 100, hitting Number 1 in late 1957, and giving the McGuires the biggest of their 29 American hits, and NorVaJak another valuable copyright.

"Sugartime", the original by Charlie Phillips and the cover by The McGuire Sisters

Unfortunately, the all-embracing grasp of the New York record business now came into play as Coral "invited" Phillips to leave Clovis and record instead under their control in New York. He did so but without success, eventually returning home to again work with Norman who secured him a contract with Columbia for which he scored a number of country hits in the early sixties.

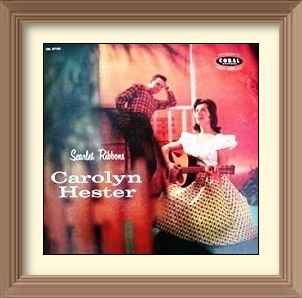

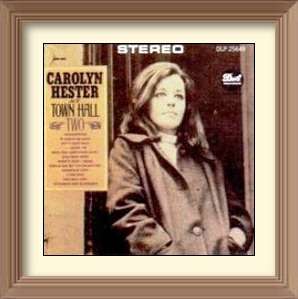

Carolyn Hester arrived at Norman's studios in 1957. Born in Waco, Texas, she had gone to New York as a teenager, and when he family moved to Clovis, she came down to visit them. Seeing her daughter's interest in folk music, Carolyn's mother phoned the local radio station asking if anybody in Clovis auditioned talent, and they recommended Norman Petty. He promptly recorded her, using Buddy Holly, George Atwood and Jerry Allison amongst others, arranging for her first album "Scarlet Ribbons" was released on Coral.

Carolyn Hester's Clovis LPs

On her inevitable return to New York, she recorded again for Coral, joined the Greenwich Village folk scene, marrying Richard Farina, before signing for John Hammond at Columbia, even persuading Bob Dylan to appear on her third album.

But she too eventually returned to Clovis, recording several live albums engineered by Petty and using members of the Fireballs as backing musicians.

By now, Buddy and The Crickets were criss-crossing the United States on major package tours, and were in demand outside of the US, and so Norman found himself travelling to Hawaii, Australia and the UK with the band, while continuing to operate the studios and struggling to keep his own Trio in the spotlight.

The "Chirping Crickets" LP and the "Buddy Holly" LP

Indeed the pace now became so hectic that one urgent recording session had to be fixed for the Officers' Club at Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma City (where the Norman Petty Trio was performing), so that Holly and his group (who were on an equally gruelling tour) could travel in to meet up with Petty and his truck-load of recording equipment, and cut some follow-up tracks. One of them was the emotive "Maybe Baby" - another Gold Disc for The Crickets.

By now, the Crickets were down to three with Niki Sullivan leaving the group, while Norman also had earlier lost from the Trio his old friend and guitarist Jack Vaughn, who had just married and was no longer willing to travel. Jack went into the insurance business in Clovis, and although he was now suffering the onset of chronic arthritis, a consequence of an earlier baseball career injury, he continued to play guitar on some of the Trio's recordings.

Even Buddy had been recruited to played guitar on one Trio recording session, and Norman had asked Sonny Curtis (who had played guitar on Buddy's Nashville sessions) to join the Trio full-time, an offer which Sonny declined.

The Crickets 1958

Although The Crickets were now riding a wave, heading into their fourth consecutive hit "Think It Over", Decca, which owned Coral Records, was of the opinion that public taste was changing and that rock & roll was declining in popularity. Decca's biggest "rock" star had been Bill Haley, and in their view, the reason he was now in terminal decline was because he had been unable to move with the times.

Admittedly neither "The Chirping Crickets" nor "Buddy Holly" LP albums had reached the US Top 40 while arguably one of Buddy Holly's finest singles "Rave On" barely scraped in to the Top 40 with a number of DJ's refusing to play the song at all, one describing it as "music to steal hubcaps by" (a quip entered subsequently into the US Congressional Record no less!). In addition, The Crickets fourth single "Think It Over" was struggling to reach the Top 20.

Norman himself now started coming under pressure from Coral to either persuade Buddy to do more ballads, or to push Holly to record in New York under their direct supervision.

Both Holly and The Crickets had signed directly with Coral and Brunswick and not with Norman himself, and so the labels could instruct either act to record picked material at the label's discretion in whatever studios the labels wished. Norman recognised that the only reason they had not done this up to now was because he was producing more hit singles in Clovis than Coral was in New York.

Norman Petty

Petty himself of course had been dealing with major labels like RCA. Columbia, Atlantic and Decca since 1954 and understood that their policy was to wrest control of acts away from independent producers as quickly as possible, so as to be better able to direct both the choice of song and choice of studios.

Seeing the changes coming down the line, Norman approached the Albuquerque Civic Symphony (later the New Mexico Symphony Orchestra) many of whose musicians were unpaid volunteers, about the possibility of hiring their string section for sessions which could be held in the Lyceum Theatre in Clovis.

Buddy was not immediately convinced that dramatic changes were required however, and when Norman tentatively suggested that he might for example record with strings, Holly turned down the idea flat.

Buddy's caution at moving into the mainstream was perfectly sensible. Although Holly was the voice of everything on Coral and Brunswick coming out of Clovis, the generally more innovative and progressive records issued under his own name had by a strange quirk of fate turned out less successful in chart terms than those released under the banner of The Crickets.

The Crickets had scored four Top 30 hits ("That'll Be The Day", "Oh Boy", "Maybe Baby" and "Think It Over") against Buddy's one ("Peggy Sue"). Even Holly's follow-up to "Peggy Sue", the beautiful and thoughtful "Listen To Me" had failed to even reach the Hot 100.

Buddy Holly photographed by Norman 1958

Rock & roll might be in decline during 1958, but even Norman was surprised by the comparative failure of "Rave On" which had been recorded in January 1958, not in Clovis, but in New York as a favour to Coral producer Bob Thiele who claimed to have put his own career on the line at Coral by insisting that "That'll Be The Day" be released.

Norman believed that he got on well with Thiele, and so when Bob asked for suggestions, Norman was only too pleased to provide them. Once in the city however, Norman's discovered that his two recomendations for the conduct of the session had been quietly ignored.

He had suggested the Pythian Temple which Decca actually owned and in which Bill Haley had recorded his "Rock Around The Clock" LP, but Coral had gone ahead and booked Bell Sound. Petty had also asked that if a vocal group had to be used to back Buddy, it should be a female rather than a male group. Coral had booked a male vocal group.

Norman was not being difficult. Although he normally decided some time after each session which track would be a Holly release and which one would be a Crickets release, he knew that this time, it had been already decided by Coral that "Rave On" would fill the final slot on the new Buddy Holly solo LP.

And if that was to be the case, then Norman, consistent to the nth degree, did not want a male chorus in case it might end up sounding more like a "Crickets record" than a "Buddy Holly record".

In spite of this, Petty was looking forward to the New York session. He had an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of the various studios' acoustics, and was aware from jazz virtuoso Bill Evans that Bell was the best "piano studios" in New York. Indeed, some years later, he again used Bell Sound to record a number of singles by The Fireballs.

Realising that under union rules, he would not be allowed act as sole producer, he offered to play on a session which would give him the opportunity of working with top guitarists such as Al Caiola and Don Arnone. Although Norman could not be the sole engineer on a union session, he was, under union rules, permitted as he put it himself to "aid the production". However, as a paid-up AFM member himself, he could of course play piano on the recording.

And of course, as an electronics buff, he was naturally curious to get a look at the masses of equipment which had been specially developed for Bell in New York, in particular their new four-track tape machine, one of which Norman hoped to place an order for.

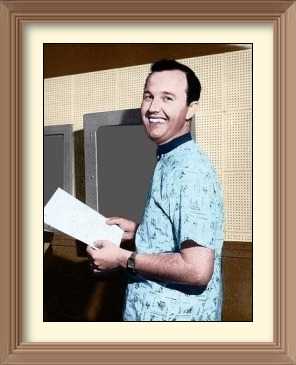

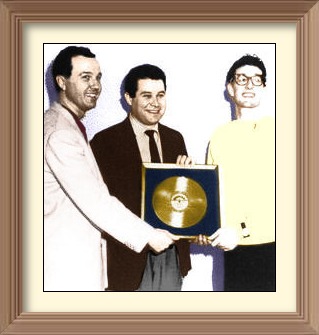

Norman Petty and Buddy Holly, receiving a Gold Disc

from Bob Thiele, Decca Records, New York City 1958

That evening, Norman was in his element, spending a long time examining the equipment in the studios, playing piano on both sides, and pronouncing the entire event "a huge success".

Oddly enough, Bob Thiele himself who had instigated the session felt it had not worked, saying:

"I think Buddy was more comfortable at Clovis. I don't think any of us felt this was a great or successful move, to record in New York".

Comfortable or not, the session had resulted in one of Holly's most iconic - even if commercially less successful recordings.

In fact, if Buddy had really seemed uneasy, it was possibly due to Thiele's choice of second song for the session. Coral's desire to push Holly towards the ballad genre had led Thiele to propose they should also record the old Frankie Laine standard "That's My Desire", penned in 1931 by Helmy Kresa and Carroll Loveday. It was not a good choice. Buddy did two takes, liked neither of them, and Coral never released the song - or at least not during Holly's lifetime.

Thiele who later visited Clovis, had this to say:

"There’s an atmosphere and a type of musician there that you just can’t get in New York. It’s calm and relaxing and there doesn’t seem to be any urgency about what you are doing. The appeal of these boys depends a lot on their simplicity. You try them in a New York session and you get a lot of wise guys breaking up that feeling."

Now, six months later, in June 1958, Norman and Buddy found themselves back in New York without the Crickets in an attempt to boost the flagging sales of "Rave On" which was still struggling to make the Top 40. It was to be a fateful visit, leading to Holly's first recording session, backed by musicians other than The Crickets.

Norman explained how it came about.

"Buddy and myself were in New York on a promotional tour and I was sitting in the office of one of Decca's top promotion executives and he told me this story about Bobby Darin. Bobby was under contract to Atlantic but his contract was about to expire and he believed that it might not be renewed. Therefore, in order to have something going for him as it were, he had recorded a song he had written called "Early In The Morning", under an assumed name, and Decca had put it out.

In fact, it was already beginning to sell.

However, Ahmet Ertegun is nobody's fool; he has great ears and of course he said "What's going on - that's Bobby Darin!" and so he filed a legal action against Decca and took over the record.Naturally the people at Decca were very sore at losing the record so I said to them - how about letting Buddy to do the song?

Anyway I called Buddy to come over, and he listened to both sides and said sure, he'd do it. He got together next day (Wednesday I think) with Dick Jacobs who was doing the orchestration of it.

It was recorded on Thursday night at the Pythian Temple studios, and on Friday, they were carrying round acetates of the song to all the key radio stations. Monday morning, Decca had copies pressed and on their way into the shops".

Buddy Holly 1958

It worked. Although Bobby Darin's original of "Early In The Morning" had already charted, Buddy's version still made the Top 30, giving Holly his biggest hit since "Peggy Sue".