|

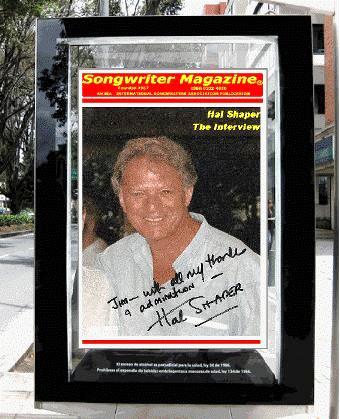

Introduction by Jim Liddane

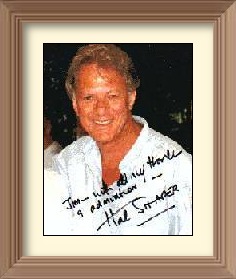

Hal Shaper is a unique figure in the music business.

Nobody else has managed to combine active careers as both writer (mainly, but not exclusively, of lyrics) and publisher (of other people's songs as well as his own), and achieve international prominence with both.

Born in the village of Muizenberg, South Africa, Hal qualified as a lawyer, but then straight away came to London to pursue his dream of being a successful songwriter.

And within ten years of his arrival in 1955, the dream had been achieved. He then formed his own publishing company, Sparta Music, and made a huge success of that, too. His writing successes started around 1959 with an Ivor Novello Award and a string of covers.

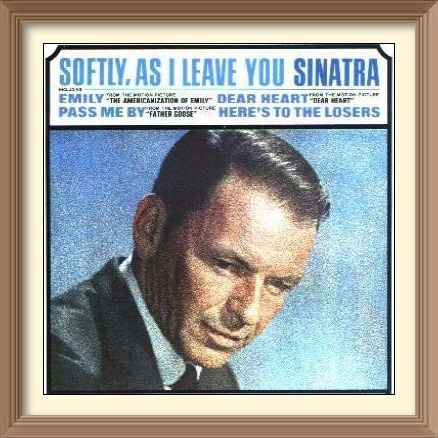

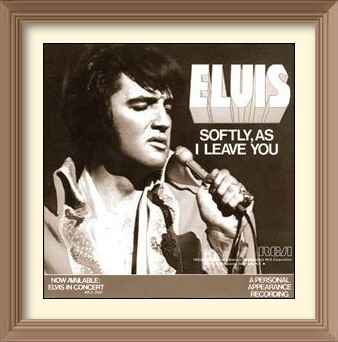

In 1962, Matt Monroe recorded "Softly As I Leave You" (Shaper's English lyric for an Italian melody) and this exploded his career on an international scale. "Softly ..." was subsequently recorded by Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Bobby Darin, Lena Home, Shirley Bassey, Howard Keel and several hundred others, and it was the early royalty cheques from this song that allowed Hal to start Sparta.

Other well known Shaper works include the enchanting "The Mysterious People", the million-plus-selling "Aranjuez Mon Amour" (The Adagio Movement Of The Concerto De Aranjuez), and the 1975 disco smash, "El Bimbo".

About 85 of his 650 recorded works have been for films, and his collaborators in this sphere have been the very best: Jerry Goldsmith, Francis Lai, Maurice Jarre, Michel Legrand, Ron Goodwin, Ron Grainer and John Williams. The films have included Sylvester Stallone's "First Blood" and "Papillon", whose theme song "Free As The Wind" was later covered with great success by Andy Williams and Engelbert Humperdinck.

Hal is one of the few people to have had a song recorded by Elton John - a hard-to-find film song called "From Denver To L.A." and other superstars to have sung his work include Bing Crosby, Barbra Streisand, Jack Jones, Vikki Carr, Astrud Gilberto, Paul Anka, Elaine Paige and Dusty Springfield.

Among his other collaborators have been Herbert Kretzmer, Tony Hatch, Les Reed, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Stanley Myers and Errol Garner.

And so to Hal Shaper, music publisher. Sparta Music began in 1964 and flowered with the Swinging Sixties. There were exclusive deals with two members of The Moody Blues - Denny Laine and Mike Pinder - leading to cuts on the band's hugely successful albums, from "The Days Of Future Passed" to "Every Good Boy Deserves Favour".

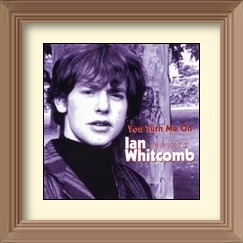

There were deals with two British acts that had great success in the States: Chad Stuart & Jeremy Clyde (7 Top 40 hits in the U.S., only one here) and Ian Whitcomb (three U.S. charters).

David Bowie came and went - but returned in the 70's at the peak of his powers. There was Vikki Carr's 1967 hit, "It Must Be Him" and The Young Rascals' classic "Groovin" in the same year. And there was reggae. Sparta signed every reggae item it could, convinced the music would break through eventually. And it did, with Desmond Dekker's "The Israelites" and Max Romeo's "Wet Dream", both in 1969 - the year when the expanding Sparta was renamed Sparta Florida.

The 70's dawned with a very valuable B-side: the one on the reverse of Mary Hopkin's million-selling "Knock Knock Who's There?" In '71, there was "Simple Game", a biggie for The Four Tops. In '72, Cohn Blunstone's superb re-vamp of Denny Laine's "Say You Don't Mind" and Dandy Livingstone's "Suzanne Beware Of The Devil" - another reggae pay-off.

There were two award-winning musicals in the middle of the decade, written by Hal himself with composer Cyril Ornadel. Firstly "Treasure Island" starring Spike Milligan; then "Great Expectations" starring Sir John Mills. Not even the punk explosion passed Sparta Florida by: they grabbed The U.K. Subs in 1979, and their 7 hit singles and 4 hit albums took the company into the 80's under the banner of The Sparta Florida Music Group.

The eighties were no different. Hit songs - like John Holt's "The Tide Is High" (a No. I for Blondie) and "Pass the Dutchie" (a No.1 for Musical Youth). And hit acts - like The Associates, who were brought down from Scotland, fed and housed, and who repaid their investment with hits like the superb "Party Fears Two". Other feathers in the SFMG cap are a strong involvement with TV, via music for "The Avengers", "Rumpole Of The Bailey", "The Sweeney" and "Dr. Who", and the administration of the American Barton Music catalogue, with over 100 great standards recorded by Sinatra and the like.

The company quickly became one of the last sizeable independents and at the time of this interview, had just celebrated its 25th anniversary.

Gerald Mahlowe interviewed Hal Shaper for the International Songwriters Association's publication "Songwriter Magazine".

When did music first make a big impression on you?

As I was born in a game reserve and living in Africa, until I was about 12 or 13, there was no question that my life was going to be in or around animals and as some wag friend of mine once remarked, "So what changed?!"

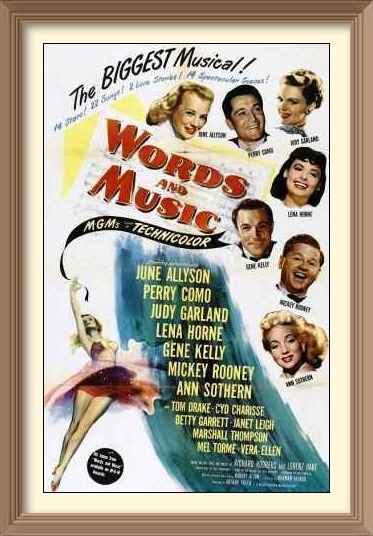

But I went to the cinema one day and I saw a film called "Words And Music", which was the life story of Rodgers and Hart, and I was so enchanted by the quality of the songs and the freshness of them, I came out saying, "That has got to be what I want to do for the rest of my life."

Strangely enough, years and years later, I found myself having dinner with Richard Rodgers in New York and my goodness, he was sharp and terribly funny! And he said to me, "Well, what brought you into this iniquitous business?"

And I said to him, as a matter of fact, I'm sure you may have heard of it - there was a film once about two songwriters that glamorously portrayed a life I thought was irresistible". He said, "What was it called?" I said, "Words And Music"! He burst out laughing and said, "You know, Hal, if I'd seen that picture, I'd have done the same thing!"

Richard Rodgers

What could you do about your ambition?

At the time, nothing! I was 13, living in a village sixteen miles south of Cape Town - population four, cinema one! - and there was no music business of any kind. I used to have to take a train or hitch-hike into Cape Town to find a little shop where they used to sell sheet music and a few records. Juke boxes were the thing in those days and they blared out the hits of the day, which were Nat King Cole, Dick Haymes and Bing Crosby - the era of the crooner.

You opted for the law?

Yes. My parents were terribly sensible and underneath it all, so was I, and when the opportunity arose for me to study law, I accepted it. But it also gave me the opportunity to write amateur shows, to work with singers, to get myself locally published - all of which I did. So by the time I went to London, I was a grown man, I was a qualified lawyer and I was earning a living. But I did pack it in, get on board a boat and go looking for a job in the music business in London!

In your early writing, had it always been lyrics only for you?

No. All my first songs, I wrote words and music, and in fact I would have continued writing both but for the fact that when I came to London and I started to get a lot of work as a lyric writer, I was working with very good composers. And I found them so good that I subdued my instincts for music, except when I was offered the job of doing both, when I was very happy to do it. In fact, on two songs that made the charts for me - one was "I'll Stay By You", which I wrote with Kenny Lynch and which won the Brighton Song Festival, and another one called "Southern Comfort", which I wrote for Berni Flint - I was involved with the music. Also when I did songs for films like "Sons and Lovers" and "Tom Jones". I did both.

You arrived in London without anywhere to go?

Nowhere to live, no job and no money. In fact, the most money that I had for the next three years was the £85 that sold my return boat ticket for!

Luckily, I made some wonderful friends. When you consider that within the first few weeks of being here, I was friendly with Michael Winner, who had just come down from Oxford, with Vidal Sassoon, with Herbie Kretzmer, who's been a friend of mine since I was a boy, with Robin Gerber, who was working at Frank Music for Frank Loesser, with Douglas Hayward, and with a lot of other very talented people including Lionel Bart and Stephen Berkoff. I really was very lucky. Nevertheless, I also worked as a dishwasher at the Troubador Restaurant for over a year, so I can't say things were that easy - but you don't notice the discomfort when you're that young and that keen.

And you eventually got a job with David Toff?

Yes, Dave was the first job I got, in Denmark Street, Tin Pan Alley as it then was, with Julie's Cafe on the corner. Those were the Tin Pan Alley days, the days when, on a major hit like "Que Sera Sera", you were still carrying about 20,000 copies of sheet music across to the Southern Music sales counter.

Denmark Street 1955 and Denmark Street 1962

Was David Toff a writer as well as a publisher?

He was not only strictly a publisher, but he told me that under no circumstances was I ever to write a song! He said there was no future in the business for writers and he meant it! I think he was probably being protective. Perhaps he was trying to tell me that publishing was a solid business whereas writing was at best ephemeral - but I already knew that.

What was your job with Toff?

Well I worked under a guy called Len Taylor and my job was as a songplugger. I got up every morning, I was out by half past eight, and I was plugging the bands every evening. In those days, song-plugging was a seven-day-a-week job, and I met everybody - I met every arranger, every singer, every orchestra leader. I knew them all very, very well indeed, and so by the time my breaks started to arrive as a writer, there wasn't much I didn't know about getting the songs to the right people.

You would take the sheet music to plug your songs?

Would you believe it? Yes. The biggest innovation in those days was the time we all got an invitation to go down to Stanhope Place (Philips), and the tape recorder happened! It meant that as a writer, I never had to sit at a piano again for three or four hours absorbing a melody so that I could write the lyric! From that point on, you could have the melody on tape and the whole business of two people sitting down together, grinding away at a tune, was over. That, for me, was a miracle. I remember that every single tape recorder that was on display at Stanhope House disappeared, and I'm happy to say that one of them was mine.

How long were you with Dave Toff?

I was there from the summer of 1955 until about August '58. I discovered writers and I discovered acts - I found Russ Hamilton while I was there - and I brought in hit after hit.

Was Russ Hamilton South African?

No, he was a Butlin's boy.

You were poached from Dave Toff by Robbins Music, I think?

Yes. Alan Holmes was a great friend of mine and I used to see him constantly, and he would always say, "You really must come and join us". And he was a fantastic boss. He and Joy Connock, his assistant, were so good with people, so good with songs, so good at matching up writers and artists.

What they did for me was create an atmosphere in which the whole business of writing was as natural as turning on a tap. They would find the tunes, they would walk in and say, "Let us have a lyric for this by tomorrow - so and so is doing it". So I already had an idea in my head even who I was writing for on a lot of the songs.

At Robbins, then, you were allowed to write!

Yes, whereas with Dave Toff! ...I think what wrecked it with Dave was when I heard one of his more famous composers playing a tune one day, and a title hit me immediately. So I walked into his office and said, "Oh, I've got a title for that!" And was greeted with frozen silence!

And the writer said to me, "What is it?" And I told him, and he said, "That's not bad! Bring the lyric in tomorrow!" So I did, and that was 1958, and that was the first Ivor Novello Award I won, for 'Best Song of The Year, Musically and Lyrically'. It was "There Goes My Lover" which is not a song that's lasted, but it was very nice at the time. There was no stopping me after that!

Robbins was the English wing of an American Company?

Yes, and I believe it was acquired by EMI eventually. But when I was there with Joy and Alan, what a work factory it was! We never stopped working and we never stopped having fun. It was seven years of the best apprenticeship anyone could have in the music industry.

Did you have to promote the songs you'd helped write?

Yes, but I was obliged to put my name down as John Harris, which was my father's first name and my mother's maiden name - but I was very happy to do that. I had no instinct towards fame or fortune; I really liked doing it. I always used to wake up thinking, "I can't imagine why everyone in the world doesn't write songs for a living!"

In the 50's, publishing was one world and records was another - unlike today, where they co-exist almost everywhere. Did you see the change begin?

Yes. The record companies ruined it for themselves. In the old days, there was an unwritten law: they had A & R men and you went to see them with the best of your songs. Now you knew that provided your song was recordable, it would go on the session, and there were usually 2, 3 and 4 songs done on a particular session. But suddenly, the record companies started to take the 'B'-sides. And the moment they went into the publishing business, we went into the recording business. They went into competition with us and it created enormous tensions. It doesn't seem possible to believe now, the outcry there was at the time. And the truth is, we were better producers of records than they were publishers.

When did this start?

It must have been the late 50's. The tragedy was that the A & R men then were real music people with a real love for songs - people like Wally Ridley, Norman Newell and George Martin at EMI, and Johnny Franz at Philips. There was no greater pleasure than to take good songs into good music people -they loved them, it transcended their job. To find a great song for whoever the artist was, was an art in itself, and they never used to toy with it.

But sooner or later -and I'm not talking about those people particularly - the concept of 'You are working for the record company, so use your talent to provide songs for the record company's own publishing company' evolved. It evolved subtly but very quickly.

The moment that happened, publishers got a bit reluctant to bring their songs to the record companies. Tim Rice, I've often heard ask, "What on earth has a publisher ever done for songs?" As a songwriter who went through those times, I say that unless you understand what the publisher's role was in those days, it's impossible for you to understand the respect I still feel for the people who amassed those old catalogues. They really did a job.

Let's move on to the start of Sparta Music. Was the idea just to publish your own work?

No, not at all. Over the years, working within the milieu we're talking about, one kept discovering marvellous talents - they were everywhere. I didn't realise that we were into what I call a 'breakaway' era - all I knew was that in 1963, the money started flooding in from the songs I'd written, the hits from 1959 onwards. And in 1962, the money from "Softly As I Leave You" started to persuade me that I had enough money, I thought, to survive for at least five years. So I made a conscious decision to start my own company, find my own talent, and create a publishing company that would be the sort of company I, as a writer, would like to work with.

Before we carry on, could you just say something about the Frank Sinatra recording of "Softly As I Leave You"? Do you know how he came to do it?

I know exactly how he came to record it. Jimmy Bowen was Dean Martin's producer, and because he was having success with Dean, he hoped that the phone might just ring with the then retired Mr. Sinatra on the line saying, "Hey kid! What have you got for me?" So he got a shoebox and marked it up 'Songs for Sinatra', and the first thing he put into it was the Matt Monro record of Softly As I Leave You". And Jimmy said to me that as time went by, "it moved further and further away and I forgot about it." He said, "Then one day the phone rang and it was the great man himself", and he heard the famous voice say, "Hey kid! Have you got a song for me?" And he said, "As a matter of fact, I do." And he walked over to the shoebox, forgetting how few items he'd put in it. When he opened it, the only record in it was Matt's! So he took it over to Mr. Sinatra, who said, "Let's Do It." What a break! The first English person who knew of its release was Don Black and he phoned me from America to say, "Hal - you've achieved every songwriter's dream. You're the next Sinatra single!"

Did you start Sparta with nothing?

Yes. My idea, essentially, was to put someone else in charge of it so that I could find the talent, write the songs, put everyone together and just go on with life. But of course it doesn't always work like that, and I found myself in charge of it and then running it. But I've always had very good help.

Your company was immediately successful, noticeably with a couple of U.K. acts that were far more successful in the U.S. than here, like Ian Whitcomb.

Yes. In fact we recorded the three hits Ian had - "Nervous", "You Turn Me On" and "This Sporting Life" - in the studios in Dublin in just one session. The studio was so small, we had to dub the tambourine on! Ian is one of the most wonderful people in the music business. He's probably the leading exponent of ragtime in the world, both as a player and an authority, and his day will come!

In 1965, a Mr. Ralph Horton came to you with an artist he was then managing - a certain Mr. David Bowie.

Yes, he did. And insisted that I take him on! Which I did, because Ralph was a very persuasive fellow and because I liked David the moment we got talking. The first time I ever saw him, David rolled up in a soldier's uniform, which doesn't sound like anything now, but then, it was spectacular. It was like having a peacock in the office and I loved it. I also had enormous affection for him as a songwriter.

His ideas were not only bright and really off-centre but he had visions which really did come from within. Over and above merely producing songs which were commercially popular, David was one of the people who really wrote what he was thinking about.

You lost him to Essex Music later on, I think?

Well I didn't lose him to Essex Music, but after David had been with me for two years, he personally asked me if we would let him go and I personally agreed to it and gave him his contract back marked 'cancelled'. And I'm very glad I did because several years later, at the height of his fame, I got a call from him, asking if I would look after his publishing again, and I did, for another three years. "Rebel Rebel" came from that, and "Heroes" and other absolutely great songs from his multi-platinum albums. And again, at the end of about two and a half years, he asked me if I'd let him go and I said yes.

I've never held him to a contract and we've never been a publishing company that has held onto songs beyond the point of either courtesy or usefulness.

Unfortunately, people don't always ask you for those reasons. They sometimes ask you for songs back because they're simply bloody-minded or disappointed, and they don't realise that in a world where contracts are far flung - in the sense that you make deals all over the world - you can't start extracting songs from your catalogue without the people you do business with feeling that you're pulling bricks out of the foundations of your relationship.

Did your earlier link with Sinatra help Sparta get the rights to the very valuable Barton catalogue?

I think it helped me in ways that are more understated than said. Because when those catalogues came up, shall we say, for grabs, every major publisher wanted them and I was one of the younger publishers who went across to California to see if I could secure them.

And what happened was that I spent my nights with the owner of the company, Hank Sanicola - Mr. Sinatra's manager for 25 years - whereas everyone else took him out for breakfast, lunch and dinner!

He was used to night-club hours and I hung around with him every evening until about 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning, when we would wind up either in his office or in a club somewhere, playing songs. He was a night time cat! And I think he was surprised to know how well I knew the songs and how much I loved them. I must say, in the face of all the competition, I was very glad that the catalogue came to us.

Tell me a little about Mike Berry (not the singer/actor), who has contributed so much to helping Sparta over the years.

He was in the office when I arrived back from a trip, once - he was hired in my absence. I liked him and I have to say that he was great fun, hardworking, with a very, very good 'street ear'. He was very good with the bands that we discovered. During the punk era, for example, he brought in the UK Subs, with whom every single was a hit and every album a charter.

The thing I liked best about him was that he had great resilience in the face of the fact that the business was changing and the conglomerates were now scoring and the smaller publishers like ourselves were finding that the rest of the smaller fish had disappeared. Suddenly there were six minnows and everywhere else you looked, there was the Great White! It was a very uncomfortable feeling.

How do you feel about that today - because you're even more on your own now?

I think there are about three publishers of our size left who are truly independent. I feel very safe now because our base has extended so broadly. I mean, we're on five chart albums at the moment. We've got cuts on Foster & Allen, on Nana Mouskouri, on "Party For The World" with Steve Walsh, on the Mirage album, on Rose Marie's album, on the "Instrumental Greats" album. We've also managed to keep the flow of recordings going - we've had very important covers in the last few years, including groups like UB40, people like Kenny Rogers, fantastic cuts.

We have also built a base of something like 10,000 hours of recorded music in our background libraries. And our latest move is the establishment of our own label, which is Prestige. We've already amassed something like 50 masters for release within the first six months. We have the new Jack Jones album, the new Julie Andrews album, the Bob Florence jazz album which is currently on the Billboard chart in America, we have the new Marion Montgomery album, and we have them for nearly all the territories in the world. We've also become much more international as well. We have an office in New York and an office in Holland.

And is it sub-publishing or administration deals in the rest of the world?

We mostly have administration deals in other territories, but in every territory we work with majors - SBK, Chappell, EMI - the very best.

Who handles your administration in the UK?

Margaret Brace runs it out of Leosong. And we have our own in-house accountants and a computer base which looks after the 15,000 works that we control.

Would you say you re now determined to stay independent?

As you know, at MIDEM this January, we celebrated our 25th anniversary and in that time, business has never interfered with the pleasures of friendships, the pleasures of travel or the pleasures of tennis! And while those things remain constant, I can see no point in changing them.

There's got to be somebody who's still accessible to writers, because nobody else is interested in songs now - they're interested in groups, they're interested in records.

But having said that, I'm 56 now and I don't know that I might not want to cash my chips in ten years down the line, because I might not have the energy then.

The business is changing. The laws are changing. The pressures are changing. It's now a business where you need enormous stamina to see yourself through the vicissitudes of it.

We've been taken over by lawyers. They've taken over to an extent that is, frankly, horrendous. Their idea of a good deal now is to squeeze the humanity and the relationship out of writers and publishers totally.

Their first rule is never to allow the parties to meet. So there's no relationship - it is strictly business. And the lawyers run it.

And you speak as a lawyer!

I speak as a lawyer. I think what they've done to the industry is enormously damaging and self-serving. I'll give you a perfect example of what I regard as utter lunacy.

Recently, cases have emerged in which the law has been established that if a writer did not have his contract vetted by a music business lawyer, it is, on the face of it, invalid. Now in the days when you and I shook hands on whatever it was we exchanged, that was a deal - that still is a deal by law.

Anything that two people agree on is an agreement at law. Barter is part of our way of life. Now how can the lawyers write into the law that unless the lawyers were involved in the transaction, there is no transaction?!

That means, for example, that the transaction of buying a packet of sugar can be set aside on the grounds that you took no legal advice! Have you ever heard of anything so ludicrous? We've reached absurdities and I don't think we've reached the final absurdities yet by any means. The only area of growth I see in the music business currently is litigation.

What advice do you have for the writer within today's very difficult industry, then?

Establish relationships. I absolutely believe that if you hang around a 'song factory' long enough, someone's going to take you in and feed you, someone will take you in and teach you, someone is going to give a break. But leave your lawyer at home. Because by and large, they create an atmosphere that pollutes the possibility of success.

My advice is: try and meet the publishers you want to have help you. Try and establish a personal relationship with a publisher or producer who is interested in your talent, anxious to ee you succeed, and pleased for you when you do. It's got to be the way.

Copyright Songwriter Magazine, International Songwriters Association & Gerald Mahlowe: All Rights Reserved

Postscript

Since 1967, we have spoken with hundreds of songwriters and music publishers, building up a huge collection of detailed interviews which is unmatched anywhere.

Click

HERE to see a list of those currently on this website. And remember, we add new ones every month!

The Main Menu

ISA • International Songwriters Association (1967)

internationalsongwriters@gmail.com

The Small Print

This International Songwriters Association 1967 site is a non-profit non-commercial re-creation of portions of the full site originally published by the International Songwriters Association Limited, and will introduce you to the world of songwriting. It will explain music business terms and help you understand the business concepts that you should be familiar with, thus enabling you to ask more pertinent questions when you meet with your accountant/CPA or solicitor/lawyer.

However, although this website includes general information about legal issues and legal developments as well as accounting issues and accounting developments, it is not meant to be a replacement for professional advice. Such materials are for informational purposes only and may not reflect the most current legal/accounting developments.

Every effort has been made to make this site as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information provided is on an "as is" basis and the author(s) and the publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained on this site. No steps should be taken without first seeking competent legal and/or accounting advice

Some pictures on this site are library images supplied by (amongst others) the ISA International Songwriters Association (1967), International Songwriters Association Limited, Dreamstime Library Inc, BMI (Broadcast Music Inc), ASCAP (American Society Of Songwriters, Authors and Publishers), PRS (Performing Rights Society), PPS (Professional Photographic Services), RTE (Radio Telefis Eireann) TV3, and various Public Relations organisations. Other pictures have been supplied by the songwriters, performers, or music business executives interviewed or mentioned throughout this website, while certain pictures are commercial stock footage of businesses and office environments generally, rather than specific images of the ISA, its personnel, facilities or members.

In any event, all images are and remain the property of the individual owners unless indicated to the contrary.

Home •

Interviews •

Writing A Song

|